Neonatal/Infant Resuscitation

Neonatal/Infant Resuscitation 4

704 - Fetal heart rate is not a good predictor of blood loss, cerebral hypoxia and hypoperfusion in ovine model of perinatal hemorrhagic asphyxia

Monday, May 1, 2023

9:30 AM - 11:30 AM ET

Poster Number: 704

Publication Number: 704.445

Publication Number: 704.445

Rebecca Valdez, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Davis, CA, United States; Evan M. Giusto, UC Davis Health, Sacramento, CA, United States; Amy Lesneski, University or California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States; Victoria Hammitt, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA, United States; Kirstie C. Tully, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Dixon, CA, United States; Emily Lane, University of California Davis Children's Hospital, Sacramento, CA, United States; Houssam Joudi, University of California, Davis, Torrance, CA, United States; Payam Vali, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, sacramento, CA, United States; satyanarayana Lakshminrusimha, UC Davis Children's Hospital, Sacramento, CA, United States; Deepika Sankaran, University of California, Davis, School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA, United States

- RV

Rebecca Valdez, B.S (she/her/hers)

Trainee

University of California, Davis, School of Medicine

Davis, California, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Fetal blood loss (such as fetal maternal hemorrhage) and hypoxia are common causes of perinatal asphyxia. The combination of hypovolemia and anemia can potentially compromise cerebral blood flow and cerebral regional oxygen saturation (CrSO2) in the fetus. Fetal heart rate (FHR) monitoring is a common method of assessing fetal wellbeing.

Objective: To evaluate the fetal heart rate, carotid blood flow, blood pressure and cerebral oxygenation during fetal blood loss leading to hypovolemic asphyxial cardiac arrest and compare it to control lambs without blood loss.

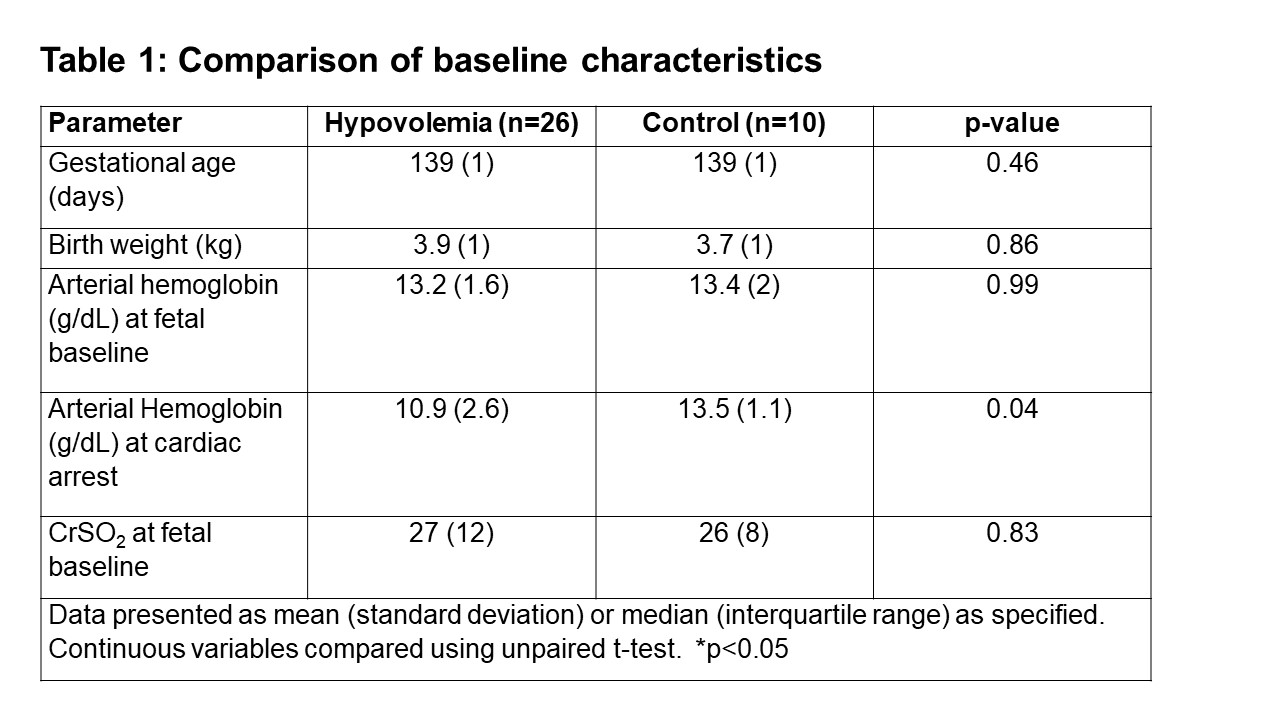

Design/Methods: Twenty-six term fetal lambs were intubated and instrumented. Exsanguination (blood draw of 30 to 45-mL/kg) was followed by cord occlusion in fetal lambs to induce hypovolemia and cardiac arrest. Ten control lambs without blood loss were included as comparison. Heart rate, carotid blood flow, systemic blood pressure and CrSO2 were monitored.

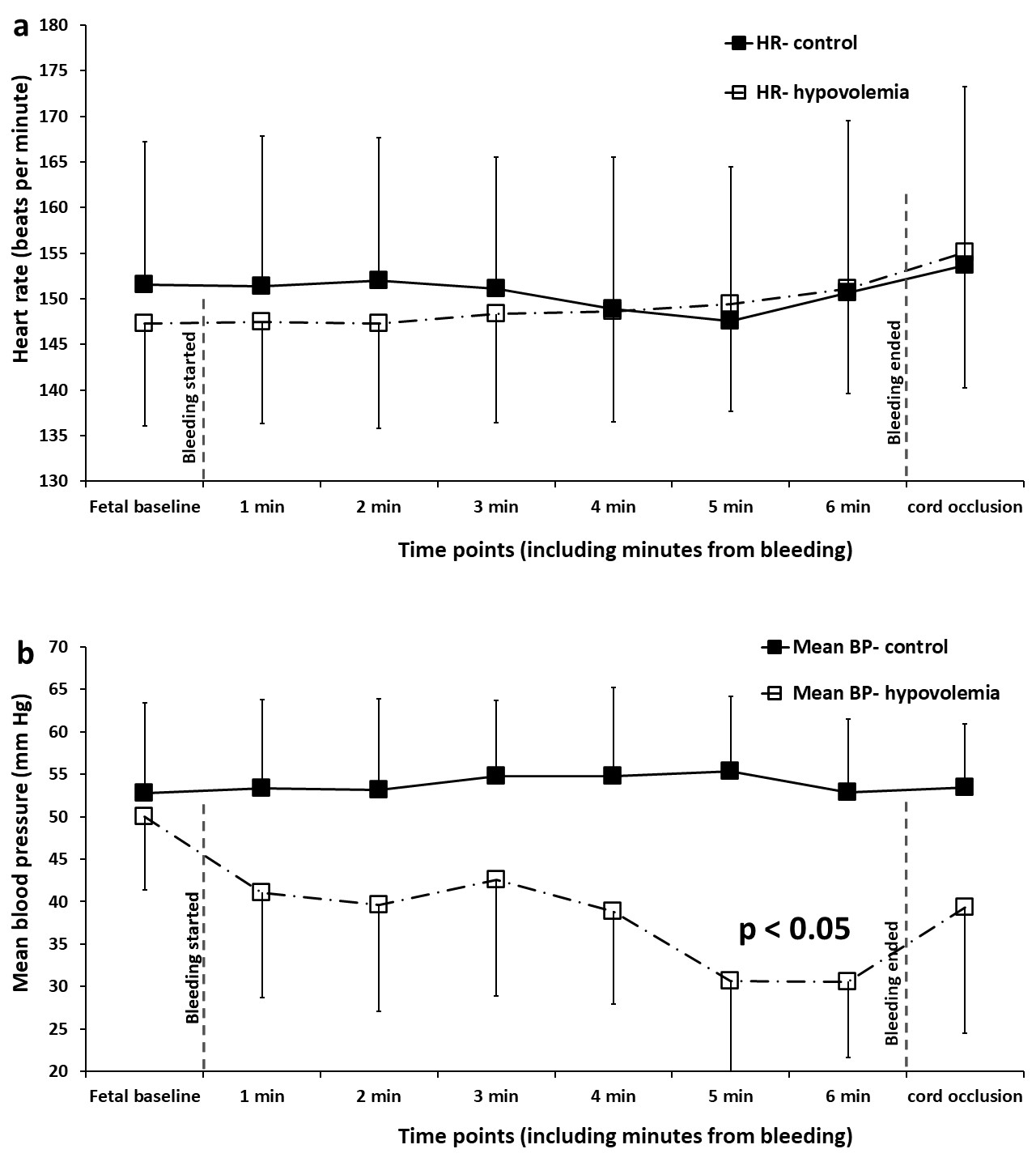

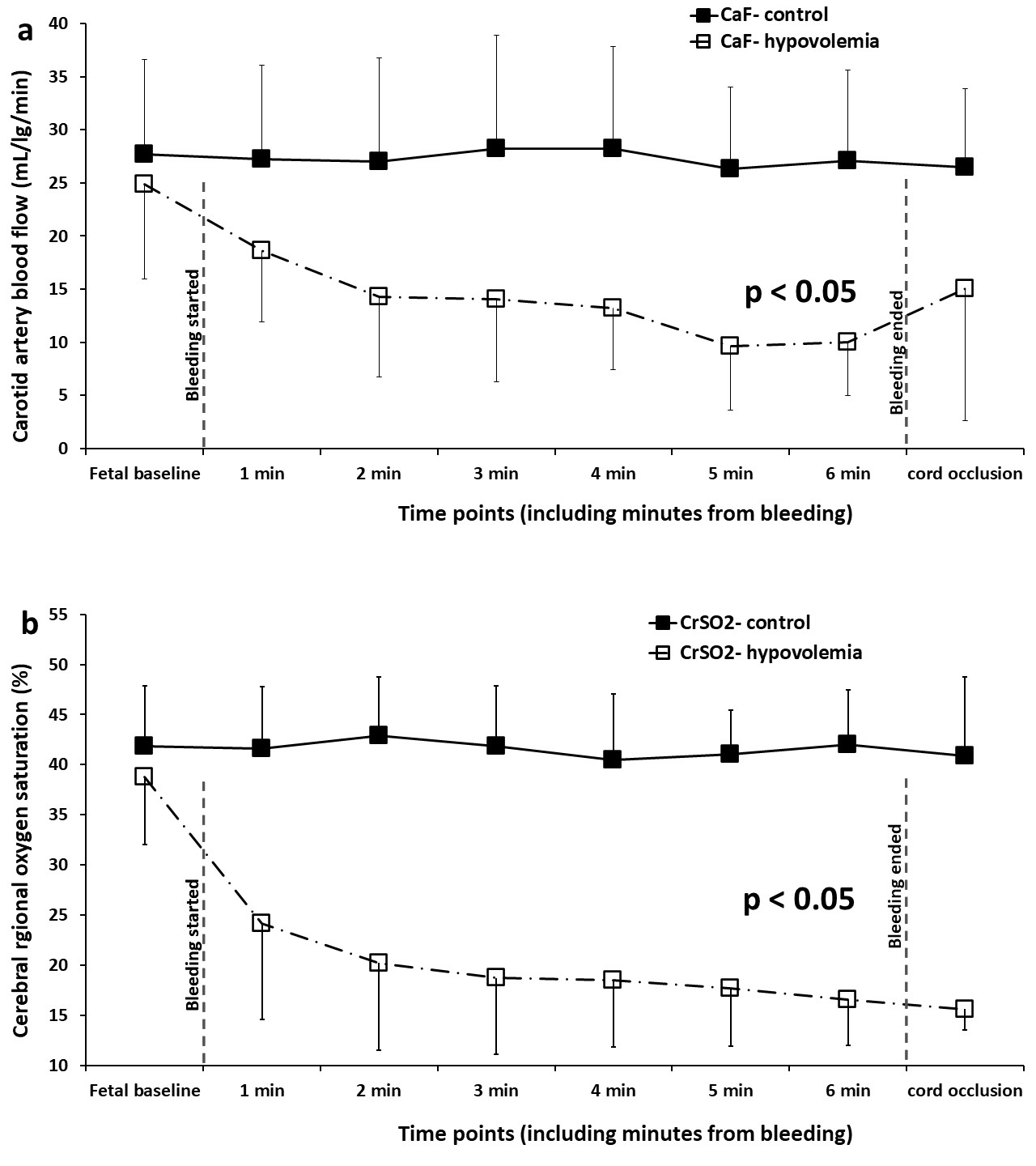

Results: Baseline characteristics were similar between the study groups (table 1). As expected, hemoglobin was lower at arrest in lambs with blood loss. Carotid blood flow (CaF) and CrSO2 significantly decreased following fetal blood loss in lambs following hemorrhage (figure 1a and 2, p< 0.001) despite minimal change in FHR. The FHR did not change despite significant blood loss in the lambs after bleeding (figure 1b) and was similar to the control lambs. Fetal blood pressure decreased during exsanguination.

Conclusion(s): Fetal heart rate monitoring may miss significant blood loss in fetus. Cerebral blood flow and cerebral oxygenation are significantly compromised by fetal blood loss. Cerebral regional oxygen saturation monitoring in the delivery room may assist in detection of cerebral hypoperfusion seen with hemorrhage. Further studies are warranted to identify fetal blood loss early and to improve resuscitative measures optimizing cerebral blood flow and oxygenation.