Medical Education: Medical Student

Medical Education 2: Student 1

471 - Improving PICU Performance and Satisfaction in Third-Year Medical Students through Distribution of PICU Handbooks

Publication Number: 471.123

- AC

Alisa Corrado, MD (she/her/hers)

Resident Physician

Rush University Medical Center

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

Medical school curriculum often excludes ICU experience, with 80% of ICU rotations offered as electives and nearly 2/3 of third-year medical students (M3) never having an ICU rotation.1,2 The transition to clerkships heightens a sense of “inadequacy and incompetence due to perceived knowledge gaps.”3,4 Despite lacking critical care exposure, 19% of USMLE Step II questions have critical care content and nearly half of fourth-year students express interest in a career in the ICU.1,2 More than 80% of medical students report using books, mainly review books, as the primary source of knowledge on rotations.5 There is currently no leading resource proven to improve M3 performance in the PICU.

Objective: To compare M3s’ confidence and perceived ability in presenting a patient on PICU rounds, forming an assessment and plan, knowledge of medical technology, and satisfaction with the clerkship before and after distribution of a PICU handbook.

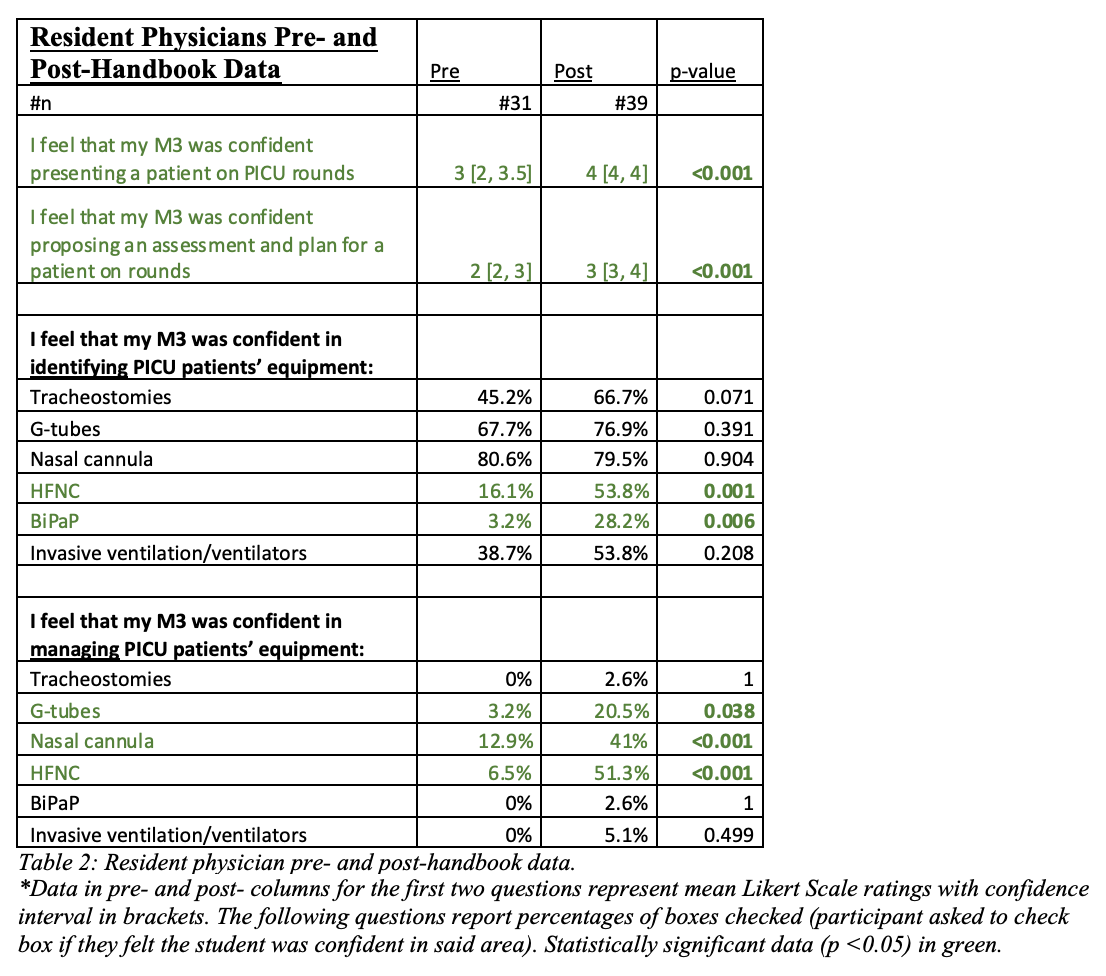

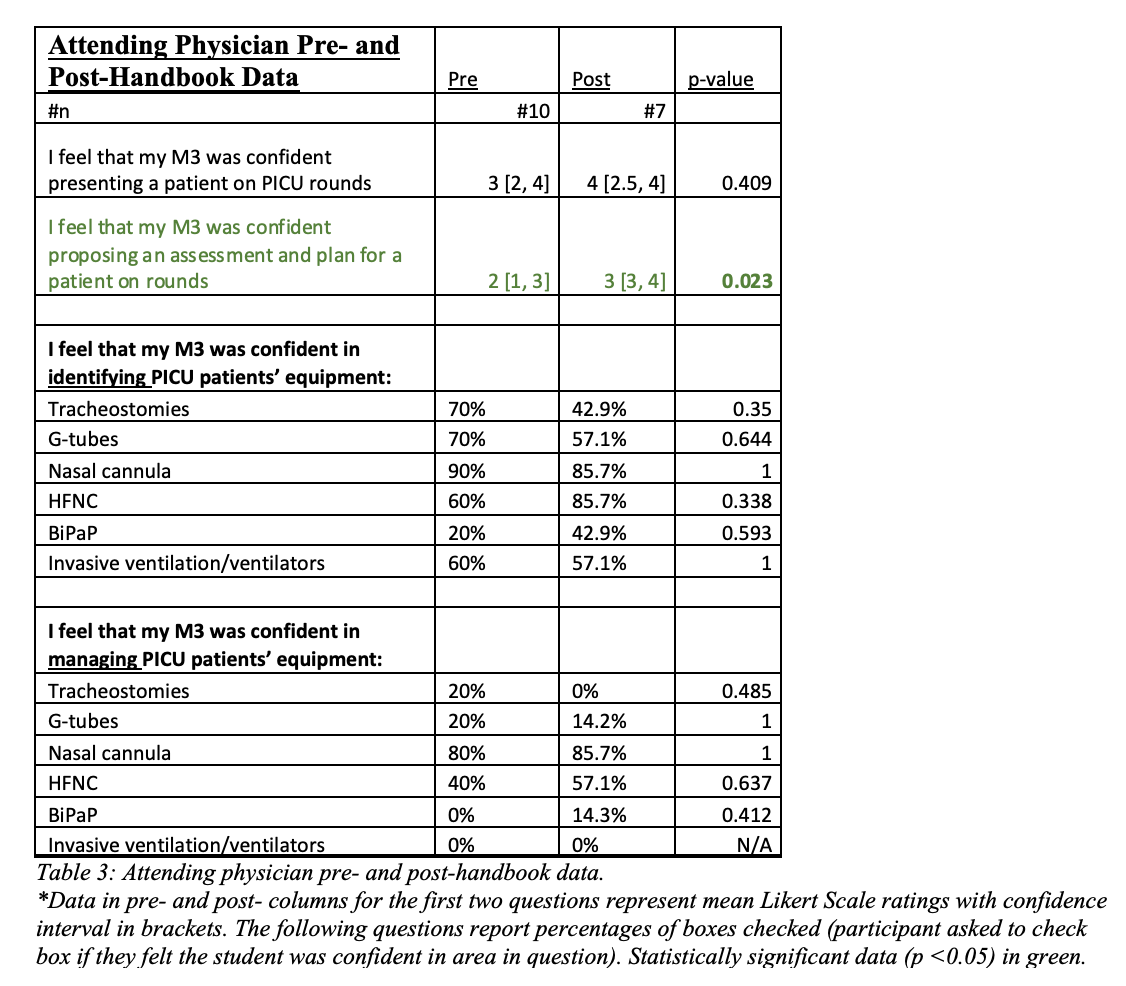

Design/Methods: 29 M3s who rotated in the PICU between 2020-21 completed a survey before creation of an M3 PICU handbook. In 2022, 34 M3s that rotated in the PICU were given a handbook and completed the same survey as the students in 2020-21. Pediatric residents and PICU attendings completed an identical survey regarding medical student performance before creation of the handbook (31 residents, 10 attendings in 2021) and after implementation of the handbook (39 residents, 7 attendings in 2022). Surveys utilized a five-point Likert scale, with 1 as “strongly disagree” and 5 as “strongly agree.” Data was analyzed using Wilcoxon Rank-Sum and Chi-square tests.

Results: The handbook improved M3 confidence in forming an assessment and plan prior to discussing with residents (p < .001) and perceived ability to identify (p 0.008) and manage (p < .001) medical technology. It helped M3s feel part of PICU team (p < 0.001) and improved clerkship satisfaction (p 0.021). Following implementation of the handbook, residents and attendings also felt students were more confident in proposing assessments and plans (residents p < 0.001, attendings p < 0.023). Residents felt students were better able to identify and manage HFNC and BiPAP machines after handbook implementation (p < 0.006).

Conclusion(s): This data showcases the utility of a standardized medical student handbook as a tool to close the perceived knowledge gap, help students feel a deeper sense of ownership of patients, and members in the care team. “Learning as membership” and “learning as ownership” shape student identity and improve the student-to-physician transition.6 .jpg)