Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health

Health Equity/Social Determinants of Health 1

513 - Inequities in Security Use

Publication Number: 513.116

April Edwell, MD, MAEd (she/her/hers)

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics

University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

University of California San Francisco

Oakland, California, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

There has been increasing attention on unequal and harmful policing practices in our country. As healthcare delivery is inextricably linked to social determinants of health, researchers have begun to explore disparities in the use of security in health care settings. To date, most of these studies have been limited to emergency departments or psychiatric facilities. The few studies focusing on security escalations among adult inpatients noted an imbalance of utilization, with hospitals disproportionally calling security on Black patients more often than their non-Black counterparts. To our knowledge, there are no studies that have explored security calls among hospitalized children and their families.

Objective:

To determine if racially minoritized hospitalized pediatric patients and their families are more likely to be assigned a security flag.

Design/Methods:

Retrospective cohort study of pediatric patients hospitalized at the University of California, San Francisco health care facilities from June 2012 to July 2021. The primary outcome of interest was any of the following security flags placed in a patient’s chart in the electronic medical record: security, history of inappropriate behavior, witnessed substance use with risk of self-harm, dismissal from a practice, and child protective services (CPS) hold.

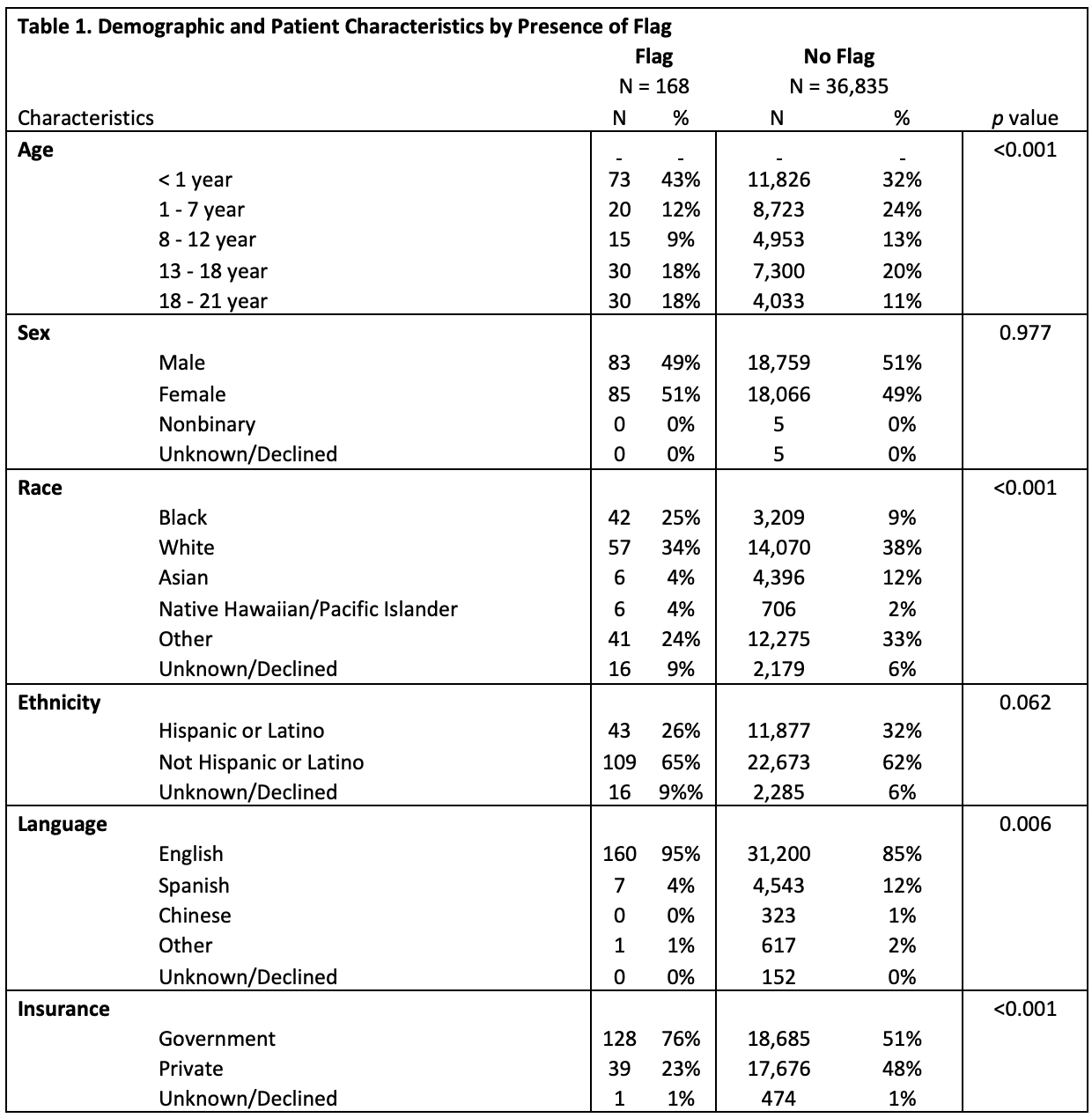

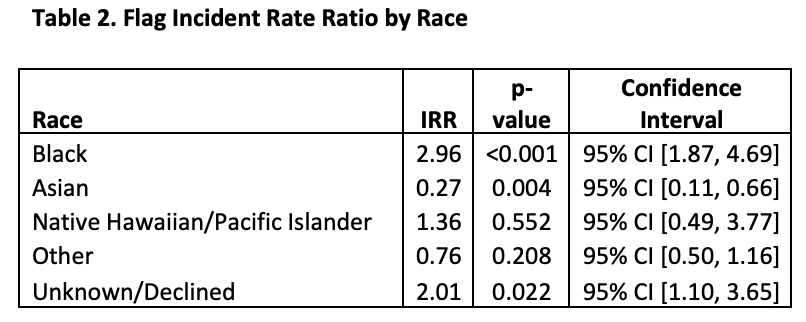

Results: Over ten years, we reviewed the electronic medical records of 37,003 pediatric patients and 168 flags. Of our sample, 9% were Black, 38% were white (see Table 1 for complete racial demographics). The median length of admission was 4 days (interquartile range 2-8). Age, race, language, and types of insurance were factors that were associated with receiving a flag (Table 1). Of the 168 patients who had a security flag, 25% were Black, 49% were male, 95% were English-speaking, and 76% with government insurance. Black children were three times more likely to have a security flag per hospital day compared to White children (Table 2).

Conclusion(s):

Our data suggest that significant racial inequities exist in the way our institution currently leverages security flags for pediatric patients and their families. Consistent with previous studies, Black pediatric patients and families are much more likely to be overly policed within the healthcare system just as they are outside of it.