General Pediatrics: Primary Care/Prevention

General Pediatrics 2

128 - How Pediatric Primary Care Providers Can Support Families of Children with Special Education Needs

Publication Number: 128.115

- MS

Michelle Stransky, PhD (she/her/hers)

Senior Research Scientist

Boston Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

Ensuring that children receive needed special education services is an essential role of pediatric primary care providers (PCPs) according to the American Academy of Pediatrics and PCPs alike. However, special education is not a clinical competency and scholarship shows that many PCPs lack confidence, knowledge, and training in this area.

Objective: To describe the gap between parents’ special education needs and pediatric PCPs ability and confidence to address those needs.

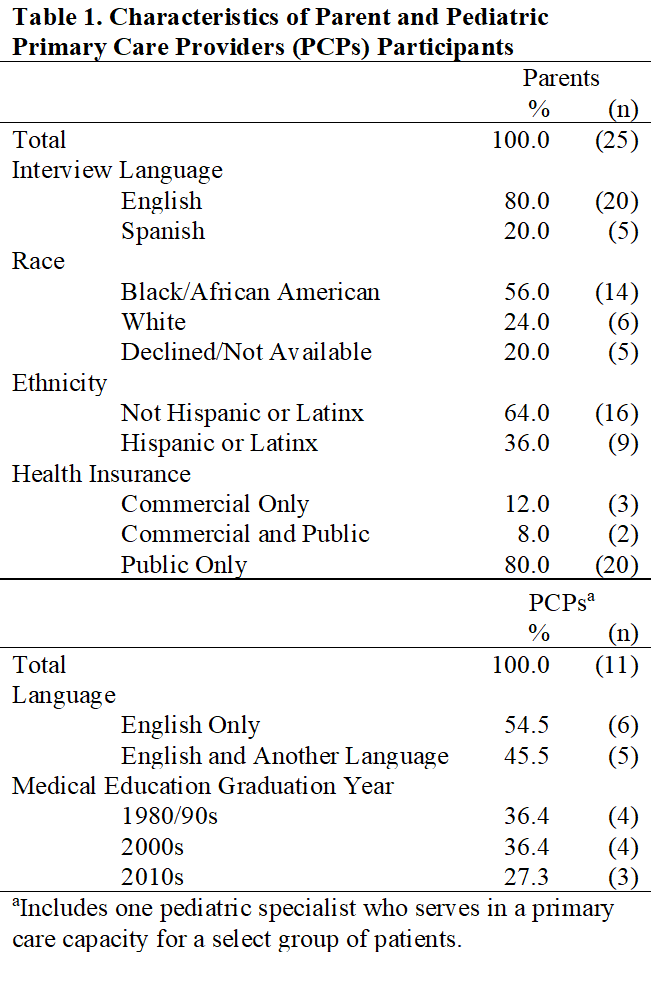

Design/Methods: These findings come from an evaluation of a primary care-embedded special education clinic. English- and Spanish-speaking parents who used the special education clinic were recruited via phone to participate in semi-structured interviews about their experiences with schools and interactions with the special education clinic. One Spanish-speaking co-author interviewed Spanish-speaking parents. Pediatric PCPs at our institution were recruited via email for semi-structured interviews and surveys regarding their knowledge, perceived responsibility, barriers to, and confidence in providing special education support. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed for thematic analysis in NVivo.

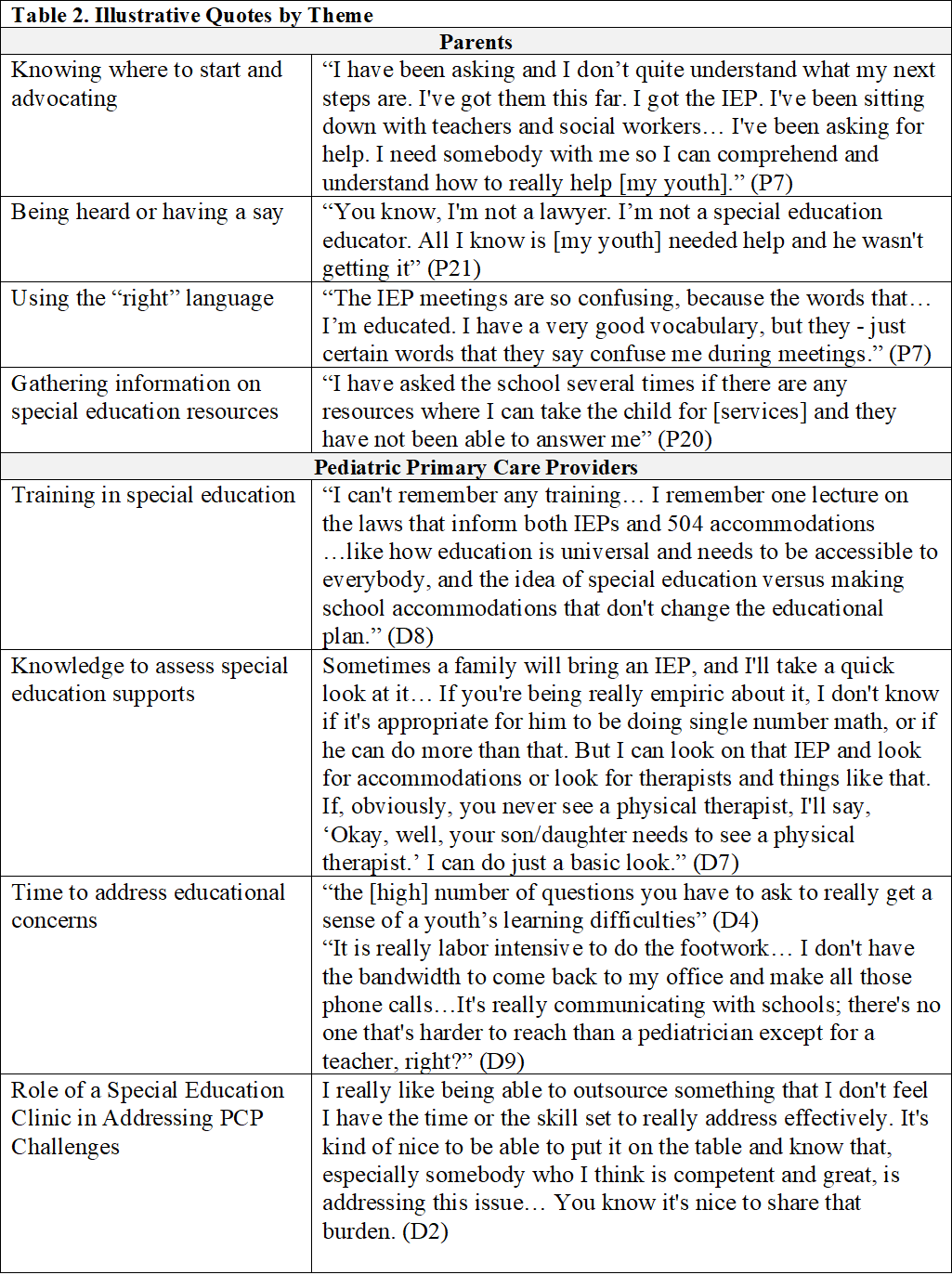

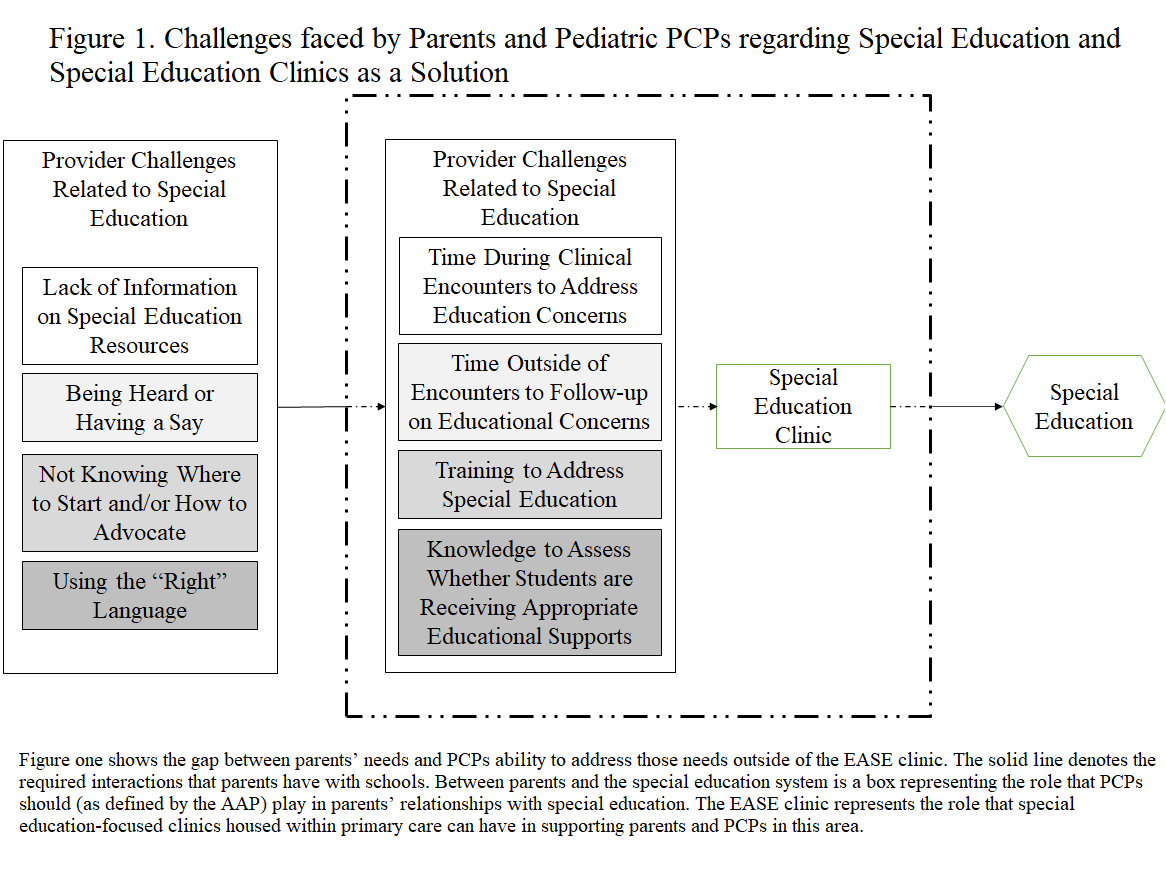

Results: Eleven PCPs and 25 parents participated (Table 1). We summarized the gap between parents’ special education needs and PCPs ability to address those needs in Figure 1. The box represents the responsibilities that PCPs have regarding special education. Parents revealed four challenges with special education: 1) knowing where to start and how to advocate, 2) being heard or having a say, 3) using the “right” language, and 4) gathering information on special education resources. On surveys, most PCPs reported responsibility to identify youth needing special education, assist parents to obtain services, share diagnosis-specific documentation, and explain processes to parents. PCPs disclosed three barriers in interviews: (1) training, (2) knowledge to assess support appropriateness, and (3) time to address concerns. PCPs reported that the special education clinic provided expertise that reduced the burden of special education responsibilities. Illustrative quotes are in Table 2.

Conclusion(s): Closing the gap between parents’ and PCPs’ needs regarding educational concerns in primary care is essential to improving care outcomes. However, PCPs do not have the resources (e.g., time) to address educational concerns and PCP-level interventions (e.g., training) will not solve systemic resource issues. Systematic efforts (e.g., special education clinics) are a feasible solution.