Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: Screening & Assessment

Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 3

407 - Predicting Engagement in Early Intervention: Results from the Smart Beginnings RCT

Publication Number: 407.206

.jpg)

Katherine L. Guyon-Harris, PhD, LP (she/her/hers)

Assistant Professor

University of Pittsburgh/UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

Early intervention (EI) improves outcomes for children with developmental delays (Shonkoff et al., 2000), but access gaps disproportionately affect children from racial/ethnic minorities and low-income families (Feinberg et al., 2011). Understanding factors associated with EI referral and service delivery can identify inequities in early care systems and inform intervention targets.

Objective:

This study examines whether parenting factors previously linked to EI service receipt (e.g., motivation and involvement; Jimenez et al., 2014), together with demographic characteristics (e.g., race) are related to rates of EI evaluation and service delivery for families with low incomes.

Design/Methods: Data for this study were drawn from the Smart Beginnings (SB) RCT, with sites in NYC and Pittsburgh, PA. SB is a tiered intervention integrating a universal parenting program delivered in primary care clinics with a selective parenting program for families with additional risks. Participants were 403 children and their mothers from Medicaid-eligible households. In NYC, families were primarily Hispanic/Latinx (84%) and in Pittsburgh, 90% of families were African American/Black. Data were collected at the age 4-4.5 year assessment. Primary outcomes were mother reports of EI evaluation and receipt of services. Predictor variables were mother reports of cognitive stimulation (STIM-Q; Dreyer et al., 2009) and desire to change their parenting (Parenting Your Toddler Scale; Guyon-Harris et al., 2022).

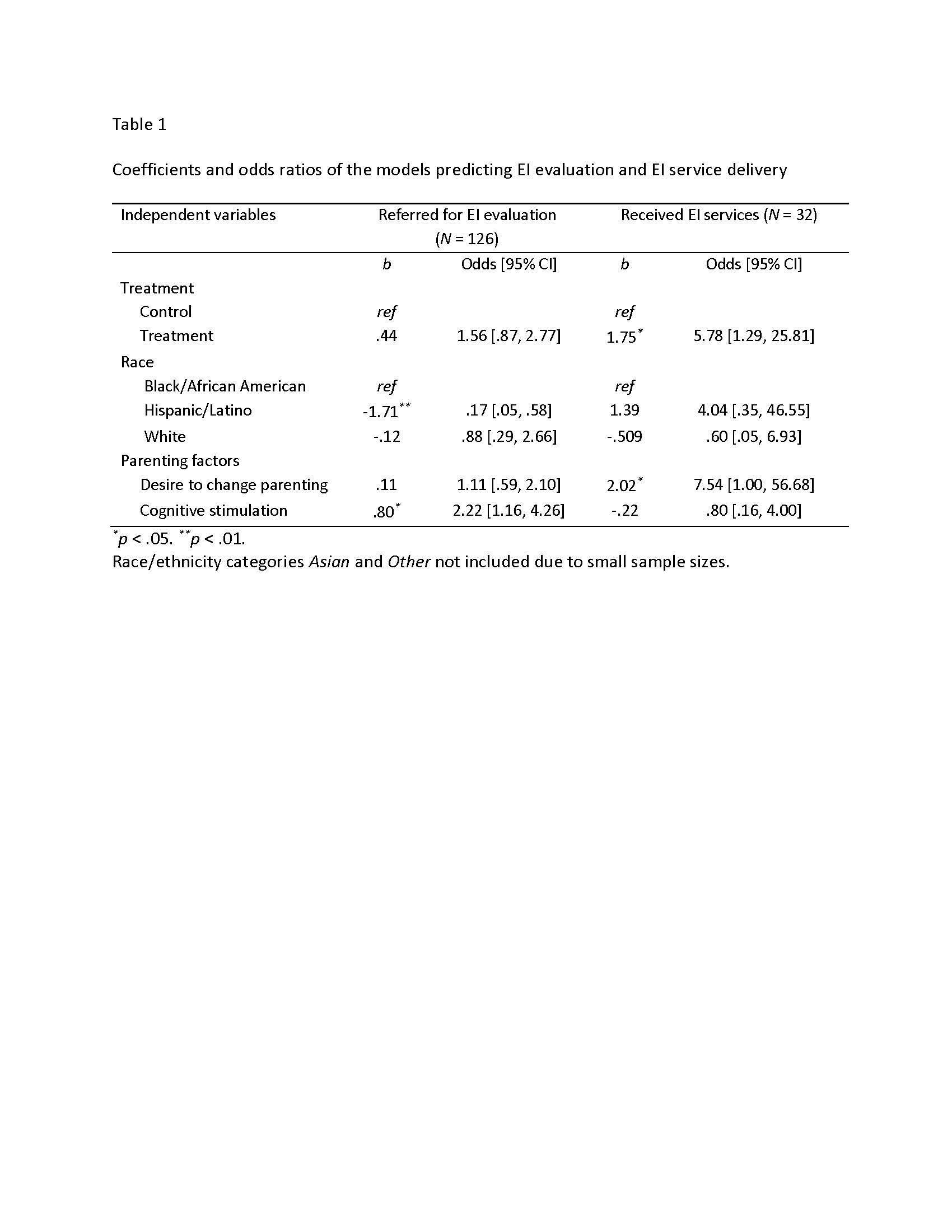

Results: Across sites, 69% of mothers reported that their child had an EI evaluation, and 25% of those received services. Two logistic regressions examined associations between parental cognitive stimulation and desire to change parenting and (a) EI evaluation and (b) service delivery, controlling for race and intervention status. For each analysis, treatment group and race/ethnicity were entered in blocks before parenting variables to ascertain the best fitting model (see Table 1). For EI evaluation, being a Hispanic/Latinx child (and living in NYC by proxy) decreased odds of receiving an evaluation compared to being Black (and living in Pittsburgh), while higher parental cognitive stimulation at home was positively related to evaluation. For EI service provision, being in the intervention group and having higher desire to change parenting increased the odds of receiving services.

Conclusion(s):

Results show relatively low rates of reported EI service delivery in this low-income sample and variation by race/metropolitan area. Parenting influences will be discussed in relation to EI practice and policy recommendations.