Hospital Medicine: Systems/Population-based Research

Hospital Medicine 4

508 - Prevalence of Social Determinants of Health Screening and Strategies among Children’s Hospitals

Publication Number: 508.221

Matthew S. Pantell, MD, MS (he/him/his)

Assistant Professor

University of California, San Francisco, School of Medicine

San Francisco, California, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

Social risk factors, such as food insecurity and housing instability, are associated with a variety of adverse health outcomes. Consequently, the American Academy of Pediatrics and Children’s Hospital Association endorse screening for social risks in clinical settings. However, little known about the landscape of these screening practices in pediatric inpatient settings.

Objective:

To understand existing social risk screening practices, strategies to address identified risks, social risk documentation practices, and outcomes related to social risk screening in children’s hospitals.

Design/Methods:

We analyzed social risk screening questions from hospitals responding to the 2021 American Hospital Association Annual Survey. We defined children’s hospitals as those endorsing that their hospital primarily restricts admissions to children. To adjust for nonresponse rates, we constructed weights using a logistic regression to predict responding to the survey based on hospital characteristics. We weighted answers using the inverse of the likelihood of response to extrapolate the sample to all acute care children’s hospitals in the US. We calculated the weighted percentage of hospitals answering each question and used Chi-squared tests to compare rates of outcomes based on hospital bed size, ownership, Medicaid status (being in the highest quartile of proportion of Medicaid patients served), teaching status, and region.

Results:

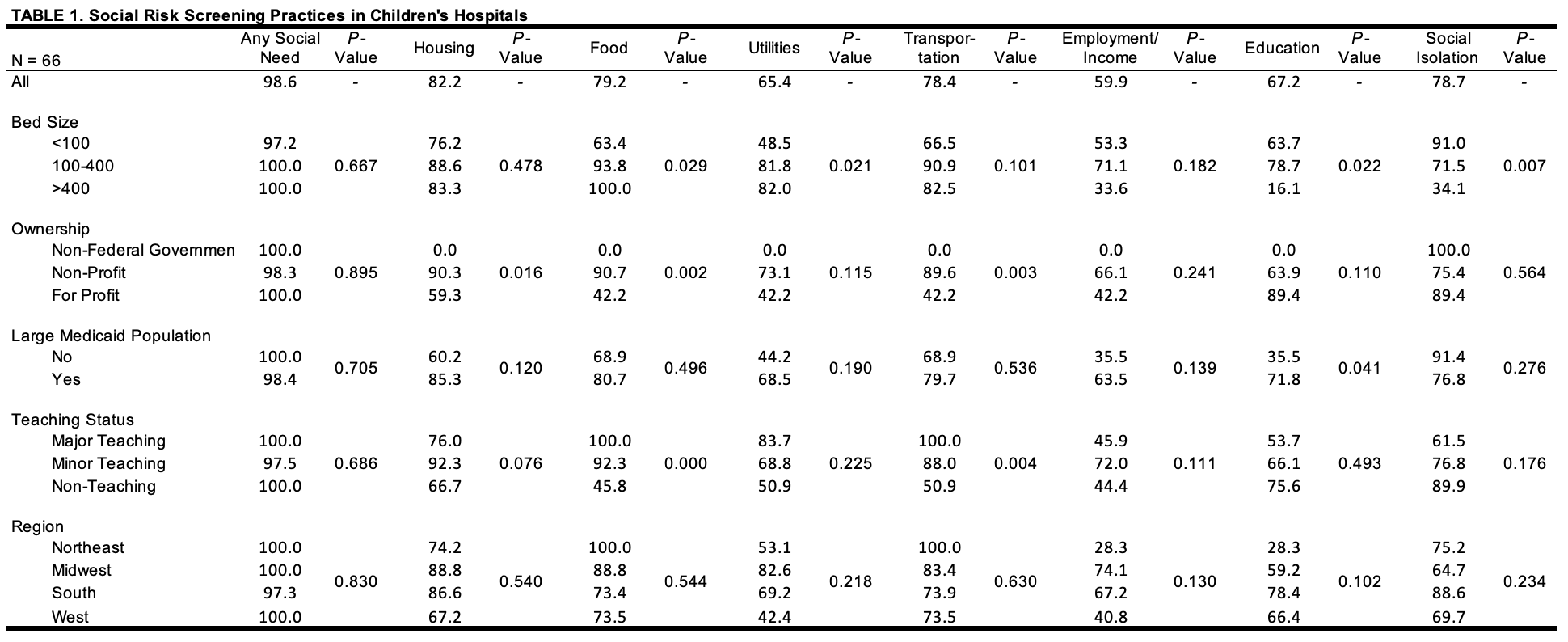

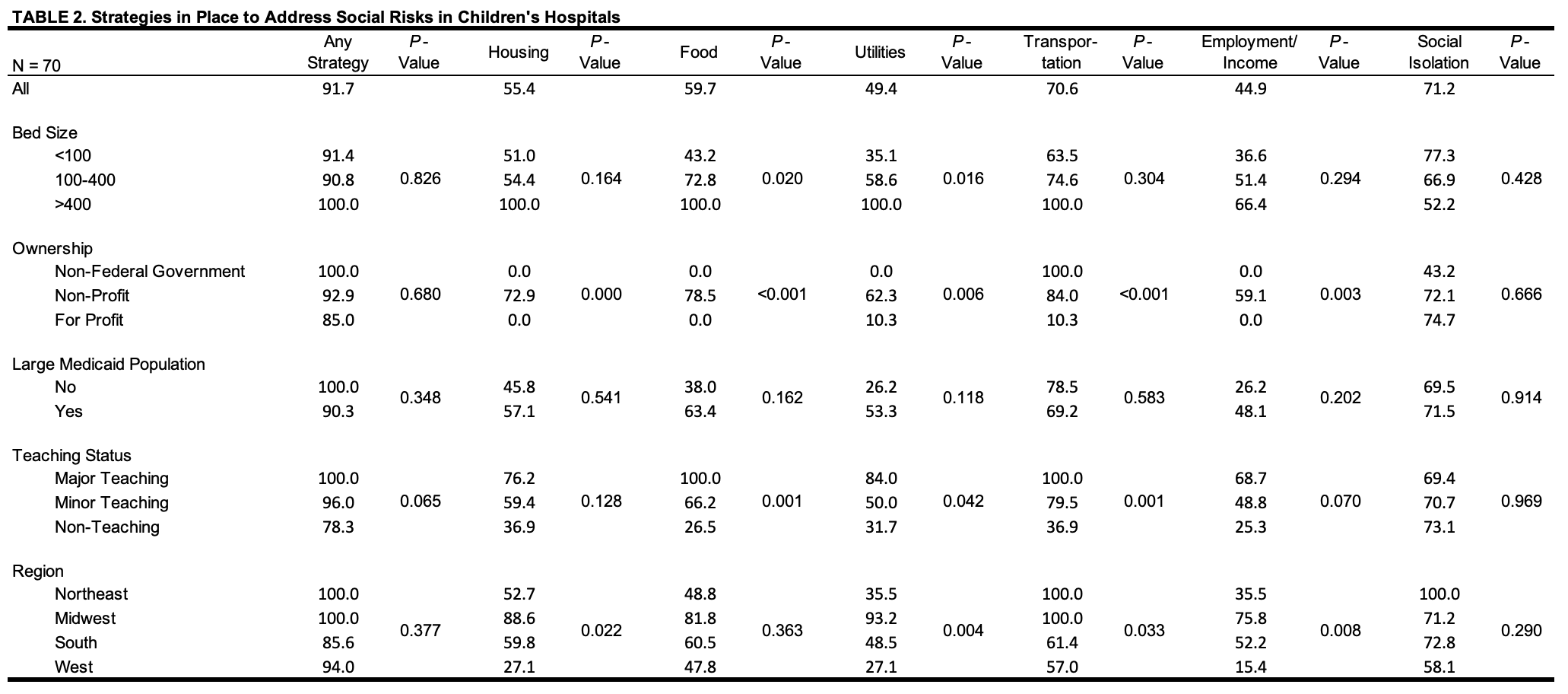

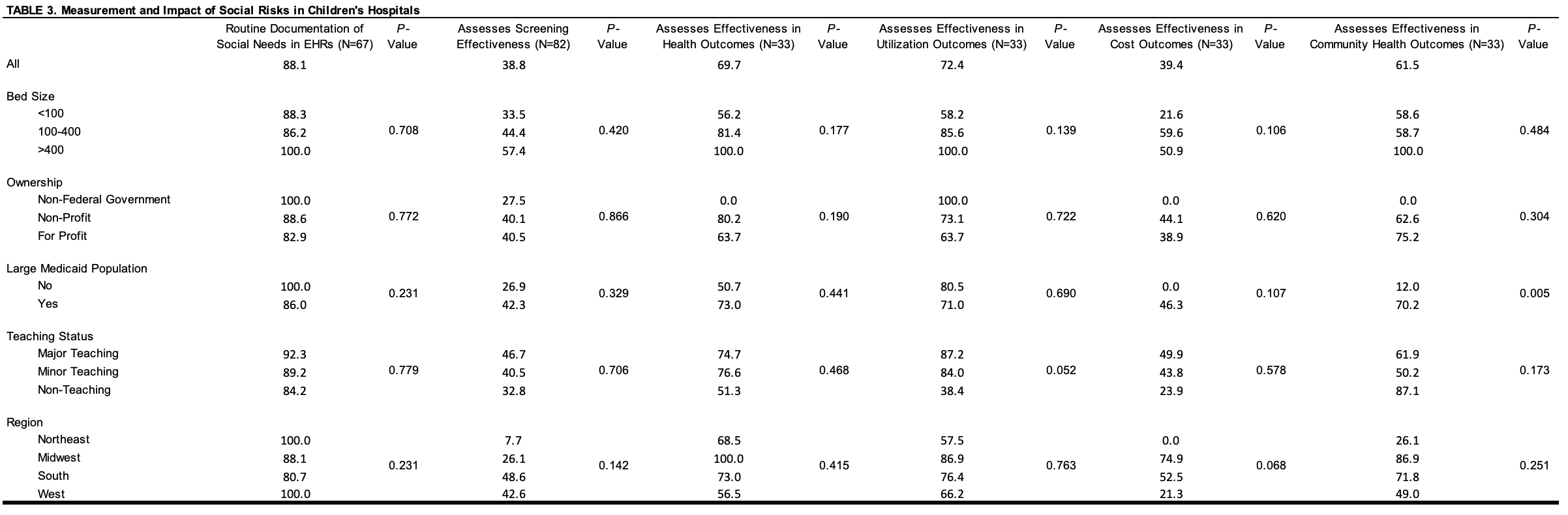

Of 94 children’s hospitals, between 33-82 answered questions related to outcomes of interest (depending on the question). 98.6% of children’s hospitals reported assessing patients for at least 1 social risk, ranging from 59.9% assessing employment/income to 82.2% assessing housing security (Table 1). 91.7% of children’s hospitals have at least 1 strategy in place to address social risks (Table 2). 88.1% of hospitals document social risks in electronic health records. Only 38.8% of hospitals collect data assessing the effectiveness of social risk screening on outcomes. Among those collecting data, 69.7%, 72.4%, 39.4%, and 61.5% found that social risk screening improved health, utilization, cost, and community health outcomes, respectively (Table 3). There was some variation in screening activities by hospital bed size and ownership (Tables 1 and 2).

Conclusion(s):

We found that nearly all children’s hospitals report screening for at least 1 social risk and many have strategies to address social risks; fewer track screening effectiveness. This is the first study of which we are aware assessing social risk screening and intervention practices in a national sample of children’s hospitals.