Medical Education: Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

Medical Education 8: Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion 2

558 - Addressing Race, Culture, and Structural Inequity in Medical Education: A Guide for Revising Teaching Cases

Publication Number: 558.23

Sanjana I. Mathur, MBBS (she/her/hers)

Resident

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Norfolk, Virginia, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Studies demonstrate that educators and cultural competency-based curricula may unintentionally reinforce stereotypes. Racial, gender or cultural stereotyping of patients by medical educators can result in delayed or missed diagnoses and contribute to poorer patient outcomes.

Objective:

Trends were assessed to see what messages were conveyed using the data collected and how this perpetuated patient biases from a provider perspective.

Design/Methods:

145 Cases from online learning platform used for US medical school students was analyzed. Different components of the case presentation including the patient introduction, history of presenting illness, details of patient education, and associated images were evaluated for portrayed behaviors and sociodemographic information. This included gender, age, race, the number of mentions of race in the case, socioeconomic status, upstream factors, cultural influences, and use of any stereotypes.

Results:

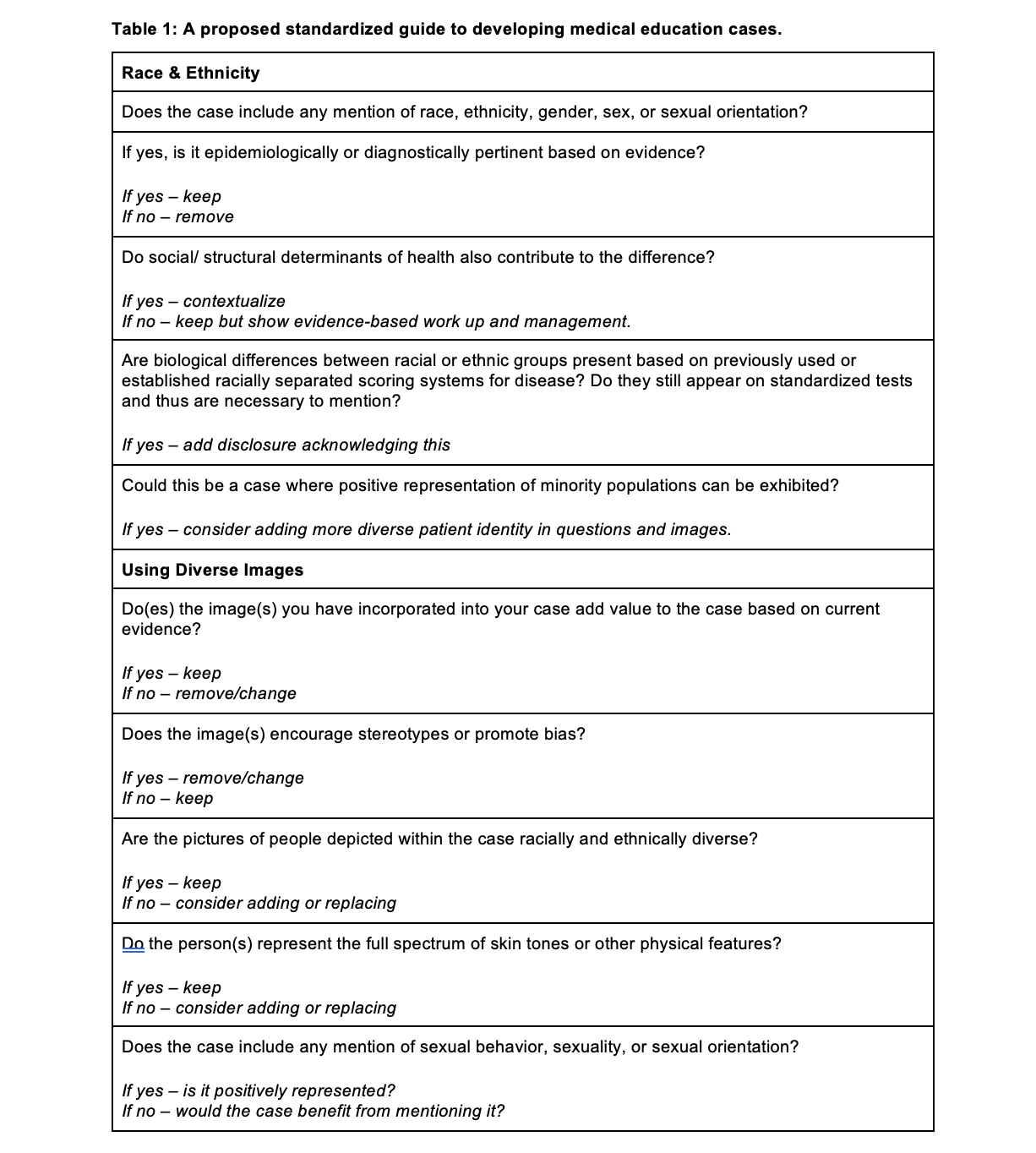

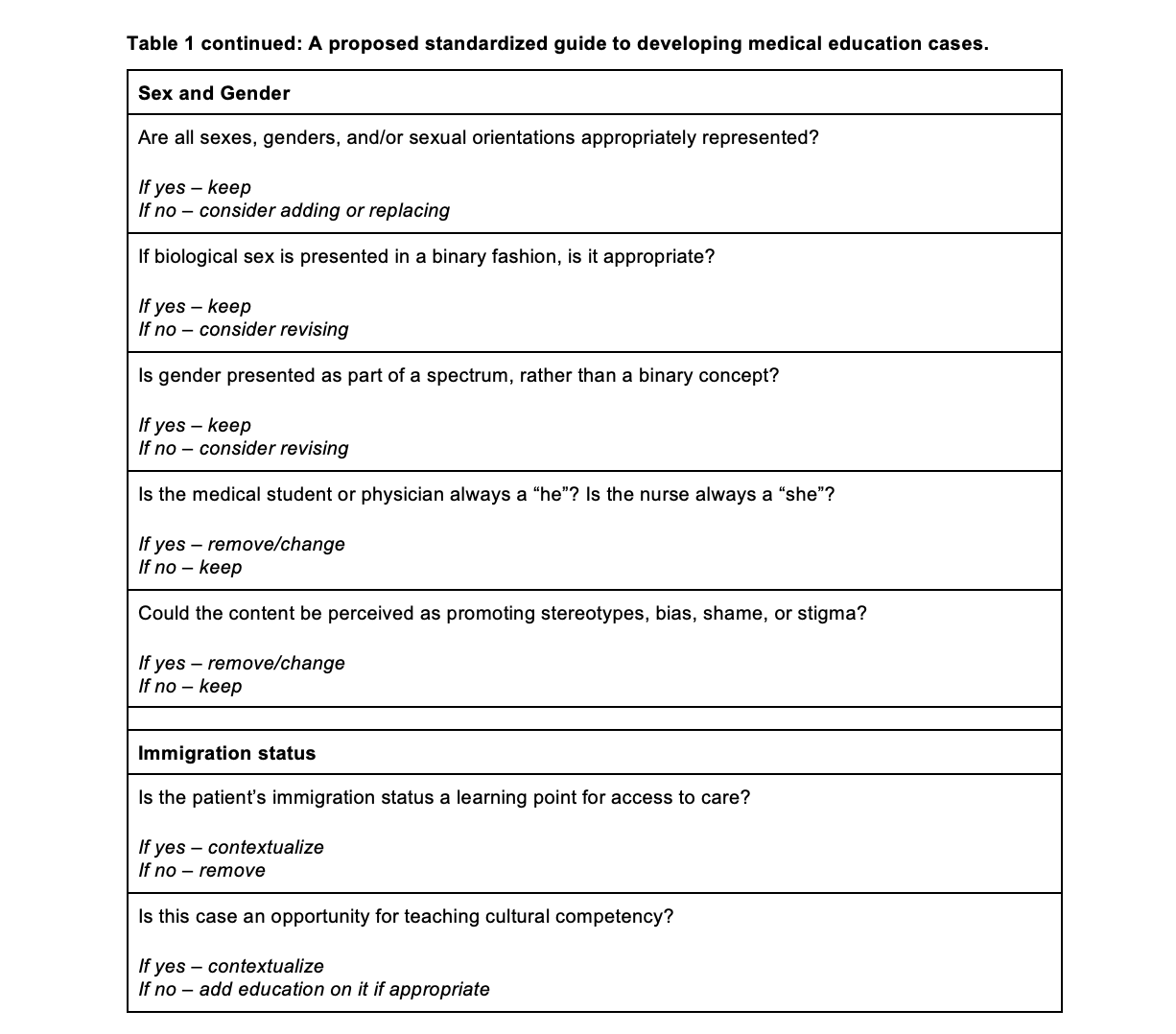

Based on qualitative data analysis five fundamental tenets became clear. 1) Cases that included patients from historically marginalized groups were often assumed to be racially or culturally different from the case author, physician or medical student. 2) The use of minority patients was often associated with pathologies associated with their race/culture as a keystone component of the history (i.e sickle cell disease only black patients). 3) Often patients from historically marginalized groups were portrayed as having unhealthy and stereotypical behavior as compared to cases associated with non-minority race patients. 4) There was little mention of outside structural or cultural factors which may impact a patient or their family’s medical decision or their access to care. 5) Images were found to represent minority populations negatively and did not represent a full spectrum of skin tones or other physical features. Overall, there was limited inclusivity and representation of marginalized groups across the range of cases. Based on these factors, a checklist (Table 1) was created to standardize the development and utilization of structurally and culturally competent cases.

Conclusion(s):

Bias-laden language is present throughout medical education curricula. While incorporated unconsciously they may result in cognitive distortions that contribute to poorer patient outcomes. With the utilization of a standardized guideline to build the cases presented to those undergoing medical training we can reduce stereotyping and incorporate health equity throughout the medical curriculum