Emergency Medicine: All Areas

Emergency Medicine 14

377 - Emergency Department adherence to infection mitigation strategies for dog bite wounds

Monday, May 1, 2023

9:30 AM - 11:30 AM ET

Poster Number: 377

Publication Number: 377.405

Publication Number: 377.405

Elizabeth M. Waltman, UMass Chan Medical School, Milton, MA, United States; David Mills, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Eric Fleegler, Boston Children's Hospital, Needham, MA, United States; Isabella G. Steidley, Brown University, Scottsdale, AZ, United States; Todd W. Lyons, Boston Children's Hospital, Wayland, MA, United States; Andrew F. Miller, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Amanda Stewart, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Michael Monuteaux, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Marvin B. Harper, Harvard Medical School, North Reading, MA, United States; Chris A. Rees, Emory University School of Medicine, ATLANTA, GA, United States; Assaf Landschaft, Boston Children's Hospital, Bergisch Gladbach, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany; Amir Kimia, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Elizabeth M. Waltman (she/her/hers)

Medical Student

UMass Chan Medical School

Milton, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: To decrease rate of dog bite wound infections, current literature suggests a 3-5 day course of antibiotic prophylaxis started as soon as possible and loose wound closure.

Objective: (1) To assess Emergency Department [ED] antibiotic prophylaxis practice for facial dog bite management. (2) Compare rates of layered wound closure for facial dog bites compared with other facial lacerations.

Design/Methods: Cross-sectional chart review performed at a tertiary care ED between 2016-2020. We reviewed notes of all patients with a facial laceration repaired in the ED, including pre-arrival notes, ED provider notes, plastic surgery consult notes, and follow-up notes. We divided notes into those addressing suture repair of dog bites versus non-dog bite facial lacerations. Data was abstracted via a natural language processing-assisted manual review. We abstracted type, timing, dosage and duration of antibiotics given for dog bites. The recommended ‘loose repair’ is poorly defined therefore we used layered wound closure for dog bites compared with other lacerations as a proxy. We estimated a multivariable logistic regression model with layered repairs as the dependent variable and dog bite versus non-bite laceration as the independent variable, controlled for age, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance status, day of week and time of day of ED presentation, laceration characteristics (length, depth, complexity) and plastic surgery repair of injury, with robust standard errors clustered on patient.

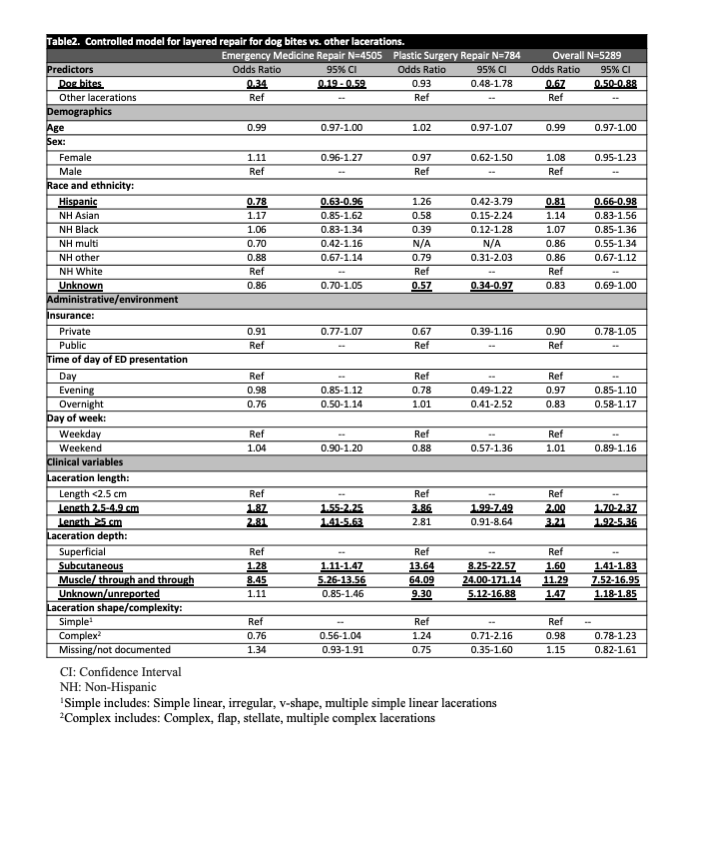

Results: 5289 patient visits were included in the study. 356/5289 (6.7%) were dog bite wounds, and 4933 were non-dog bite lacerations. While 99.2% of dog bites received antibiotic prescriptions (91.% Augmentin), 12.6% did not receive first dose in the ED, 25% of Augmentin prescriptions were < 65% of the recommended 45 mg/kg/day dosing, and 52.4% of prescriptions exceeded recommended duration (Table 1). Providers used fewer layered repairs for dog bites compared with other laceration repairs controlling for laceration length, depth and complexity; ED providers used fewer layered repairs compared to plastic surgery. Table 2 presents the layered repairs regression analysis.

Conclusion(s): While prophylactic antibiotics for facial laceration repairs from dog bites is consistently used, this study suggests variable prescribing practices related to administration timing, dosage and the overall duration of antibiotic course. Overall, single layer skin closure occurs more commonly with dog bite laceration repairs compared to other lacerations, primarily when repaired by PEM providers.

.png)