Medical Education: Resident

Medical Education 14: Resident 5

498 - Resident Exposure in Pediatric Emergency Medicine – Who, What, When and Where

Monday, May 1, 2023

9:30 AM - 11:30 AM ET

Poster Number: 498

Publication Number: 498.422

Publication Number: 498.422

Kelsey A. Miller, Boston Children's Hospital, Brookline, MA, United States; Sarah C. Cavallaro, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Alexander Hirsch, Boston Children's Hospital, Brookline, MA, United States; Joel D. Hudgins, Boston Children's Hospital, Milton, MA, United States; Galina Lipton, Boston Children's Hospital, Brookline, MA, United States; Ashley Marchese, Boston Children's Hospital, Needham, MA, United States; Sara Schutzman, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States; Rebekah Mannix, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States; Andrew F. Miller, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

- KM

Kelsey A. Miller, MD, EdM (she/her/hers)

Attending Physician in Pediatric Emergency Medicine

Boston Children's Hospital

Brookline, Massachusetts, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires pediatric emergency medicine exposure for both pediatric and emergency medicine residents. Pediatric emergency departments (PED) that provide such exposure have seen increasing volumes of patients with behavioral health complaints and large fluctuations in patient volume and length of stay, prompting alternative care models that may impact the case mix and patient volume seen by residents.

Objective: This study seeks to describe how changes in PED clinical operations impact the number and types of patients seen by rotating residents who depend upon clinical exposure to learn pediatric emergency medicine.

Design/Methods: This is a retrospective single center study of an academic PED that hosts one pediatric residency and three emergency medicine residencies. The study reviewed all patient encounters in the PED between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2022. During the study period, the PED employed up to three alternative care sites outside of the main PED. Using the electronic health record, we extracted data on each encounter including patient age, sex, triage level, ICD-10 diagnostic code and whether a resident participated in the initial evaluation. We focused on the initial evaluation because it requires interpretation of age-specific vital signs and physical exam findings as well as development of pediatric-specific differential diagnoses and management plans. We compared patients seen by residents across sites with regards to age, ESI level and ICD-10 diagnoses. Relevant pediatric ICD-10 diagnoses were identified using the PECARN Diagnosis Grouping System groups and subgroups that align with core pediatric diagnoses from the Model of Clinical Practice of Emergency Medicine.

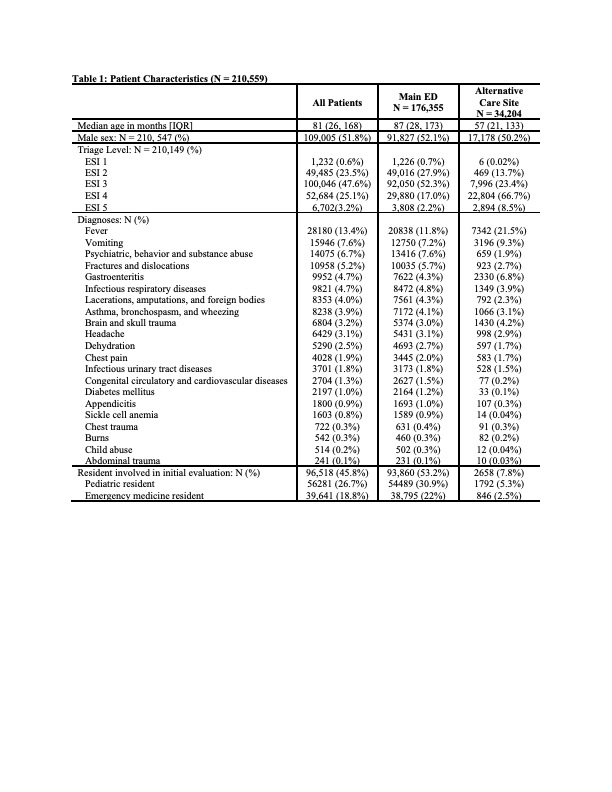

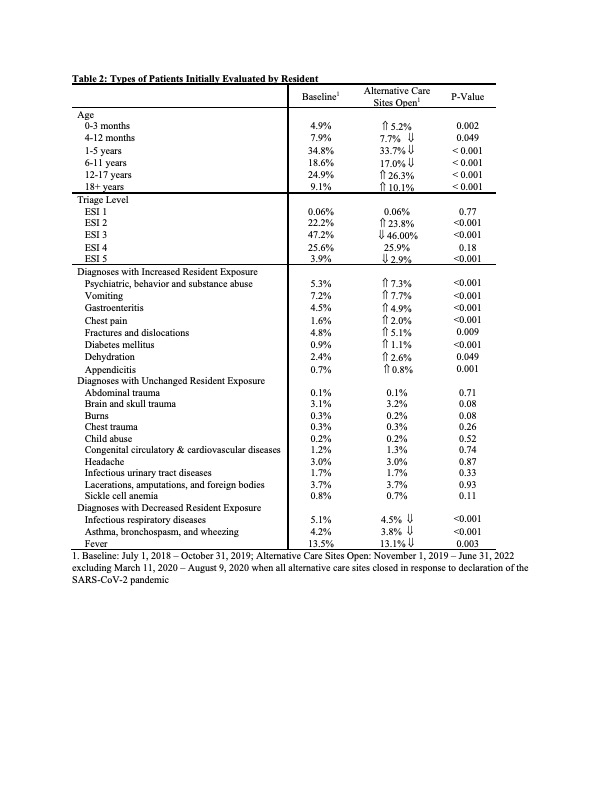

Results: There were 210,559 unique patient encounters, with 96,518 (45.8%) initially seen by a resident physician. Patients seen in alternative care sites were younger and had lower acuity ESI scores than those seen in the main PED (Table 1). Among patients seen in the main PED, 53.2% were seen by a resident compared to 7.8% in alternative care sites. Residents saw fewer patients between 4 months and 11 years, higher acuity, and fewer patients with fever and respiratory diagnoses when alternative care sites opened (Table 2).

Conclusion(s): Operating alternative care sites impacts the age, acuity and diagnoses seen by pediatric and emergency medicine residents. While such sites have important benefits for PED flow, their impact on training future physicians must also be considered.