Quality Improvement/Patient Safety: All Areas

QI 3: Subspecialty-specific QI & Patient Safety

709 - Racial disparities in failure to rescue after pediatric heart surgeries in the United States

Publication Number: 709.153

- SA

Sundos Alabbadi, Pharm.D. (she/her/hers)

Graduate research assistant

Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

New York, New York, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

Failure to rescue (FTR), defined as in-hospital mortality among patients with major postoperative complications, is a nationally endorsed quality care metric. Racial disparities exist in FTR after pediatric cardiac surgery, yet there is limited information on factors contributing to these disparities in quality of care.

Objective: To identify the trend in FTR and risk factors contributing to racial disparities in FTR after pediatric heart surgery using contemporary nationwide pediatric data.

Design/Methods:

The Kid’s Inpatient Database (KID) was used to identify 85,267 congenital heart surgeries in patients < 18 years of age in the United States from 2009 to 2019. The primary outcome was FTR. A mixed-effect logistic regression model with hospital random intercept was used to identify independent predictors of FTR. Hospital surgical volume is defined as the number of pediatric heart surgeries performed in each hospital per year. All analyses accounted for the KID design.

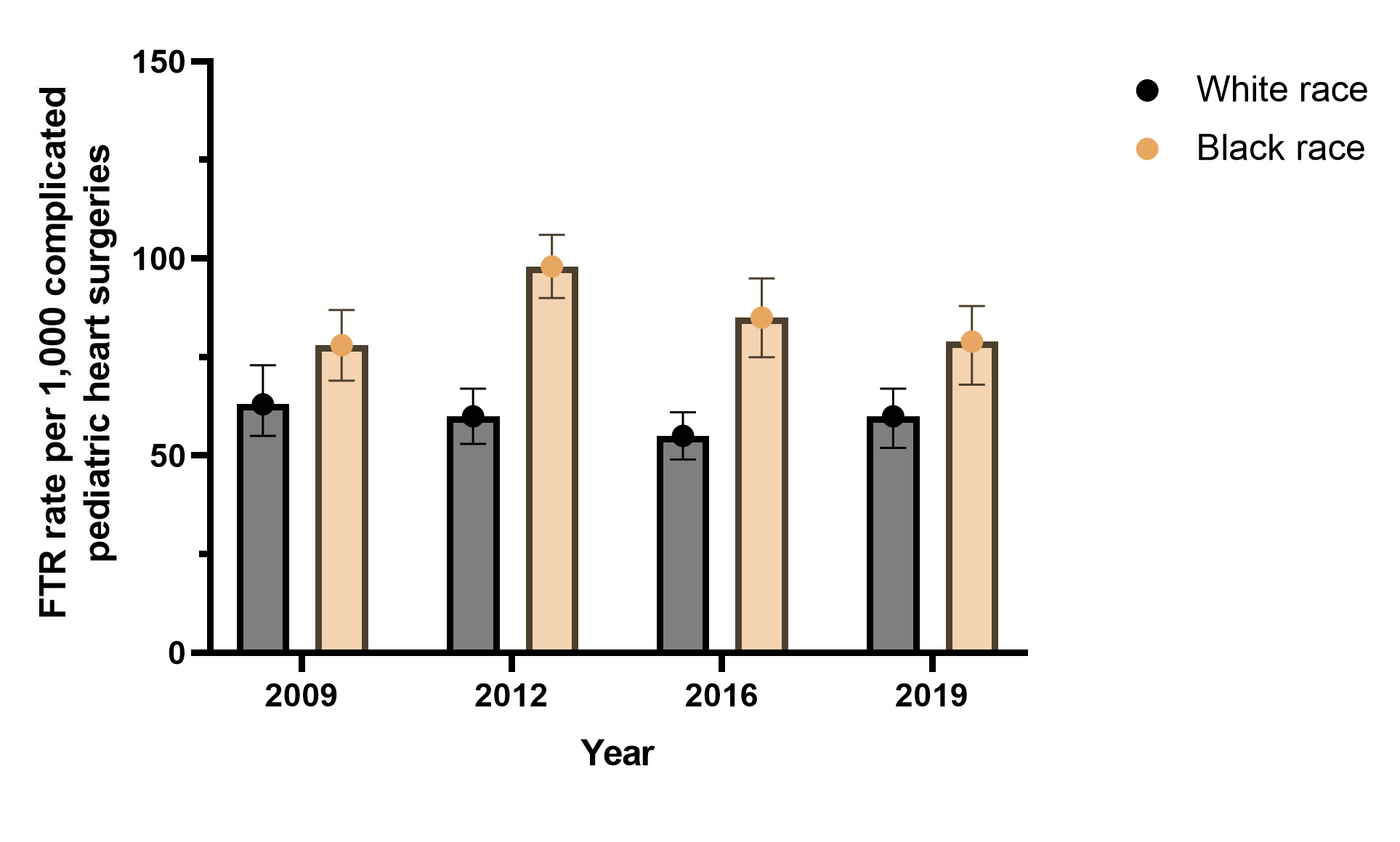

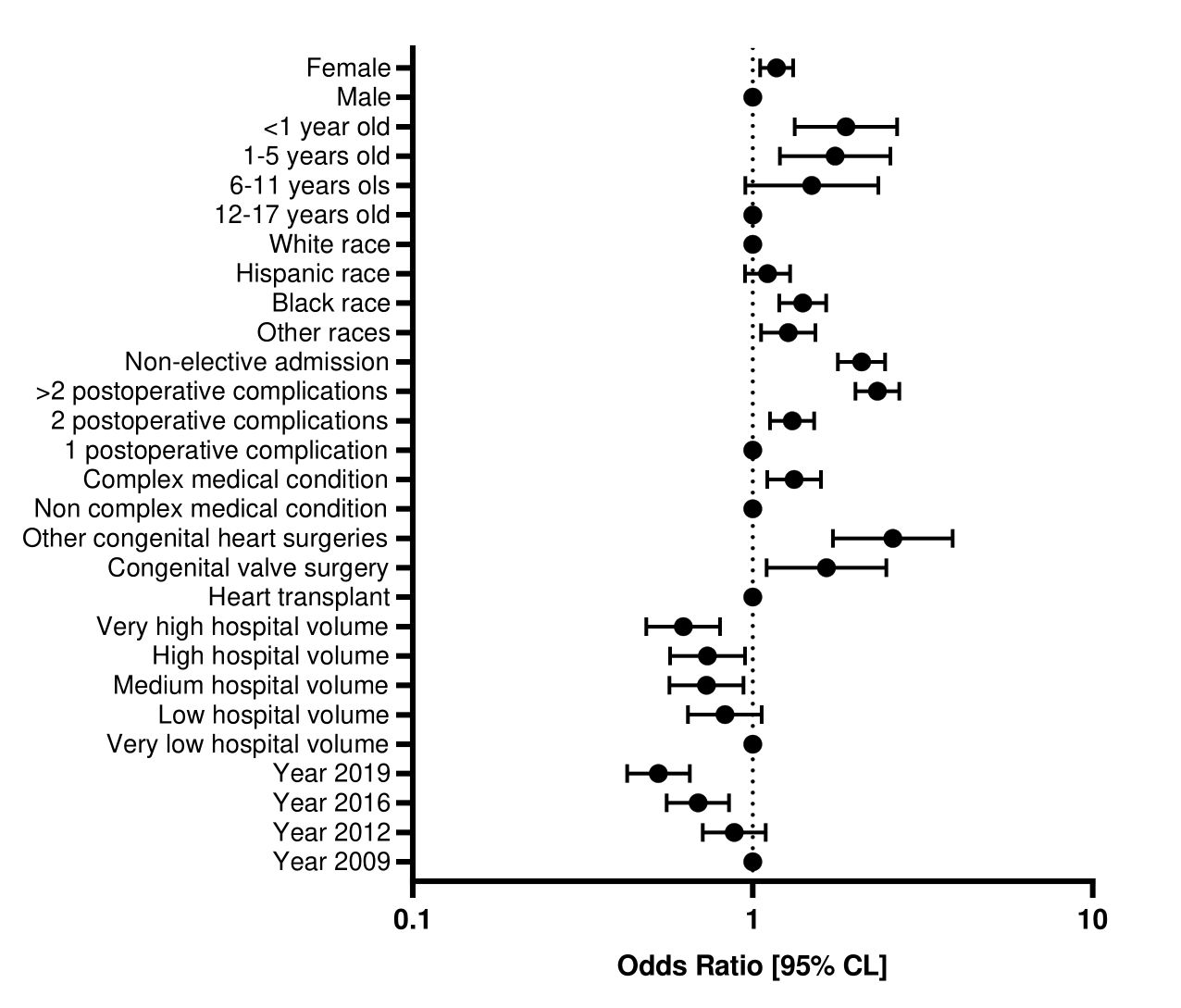

Results: Among 36,753 surgeries with postoperative complications, the FTR rate was 7.3% (n=2,515). The overall FTR rate decreased from 7.4% in 2009 to 6.3% in 2019 (p=0.02). The FTR was higher among black than white children for all years (Figure 1). The FTR rate was higher among girls (7.2%, n=1,172) vs. boys (6.6%, n=1,343), children aged < 1 (9.6%, n=2,129) vs. 12-17 years (2.4%, n=61), and those of black (8.5%, n=374) vs. white race (5.9%, n=970) (all p< 0.05). In the multivariable model, black race was independently associated with a higher FTR rate (OR 1.40, 95% confidence interval 1.20-1.65), after adjusting for other risk factors including younger age, higher medical complexity, non-elective admission, and admission to a low surgical-volume hospital (Figure 2). Higher hospital surgical volume was associated with lower odds of FTR for all racial groups, but a lower proportion of black (20.1%) vs. white (30.3%) children received surgery at high surgical-volume hospitals (p< 0.001). The racial differences in hospital admission may contribute to up to 42% of racial disparities in FTR: if black children were admitted to the same volume hospitals as white children, their adjusted FTR rate would decrease from 8.6% to 7.5%, compared to 6% for white children.

Conclusion(s):

Racial disparities exist in the quality of care after pediatric heart surgery in the United States. Black children were more likely than white children to receive care at lower surgical volume hospitals. This difference in location of care may account for almost half of the disparities in FTR.