Back

Background: In the U.S., 100,000 individuals live with sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited hemoglobin disorder. Most survive into their reproductive years but have worse morbidity and mortality during transition to adult care. During this time, adolescents and young adults (AYAs) also face reproductive and sexual health challenges related to contraception, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), potential fertility impairment, and priapism. These may be exacerbated by limited access to care and insufficient transition readiness. Yet, little is known about reproductive and sexual health counseling and practices for transitioning AYAs.

Objective: To examine rates of and gaps in reproductive and sexual health counseling for AYAs with SCD prior to their transition to adult care.

Design/Methods: A retrospective review of electronic medical records was conducted of AYAs with SCD at a Midwestern academic medical center that transitioned to adult care between 2015-2019. Abstracted data included sociodemographic information, reproductive and sexual health counseling, and screening practices across AYAs’ entire records before transitioning.

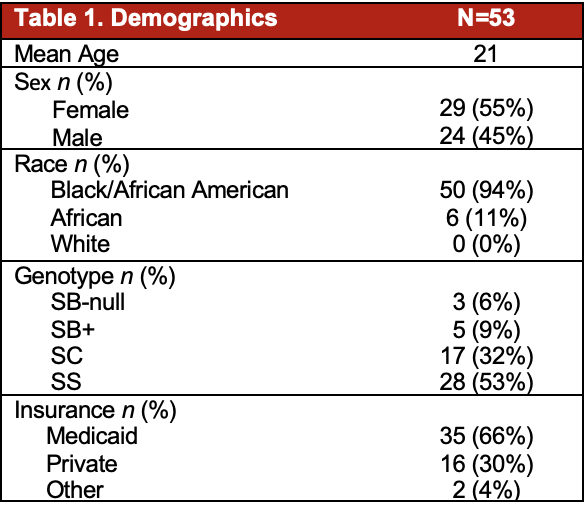

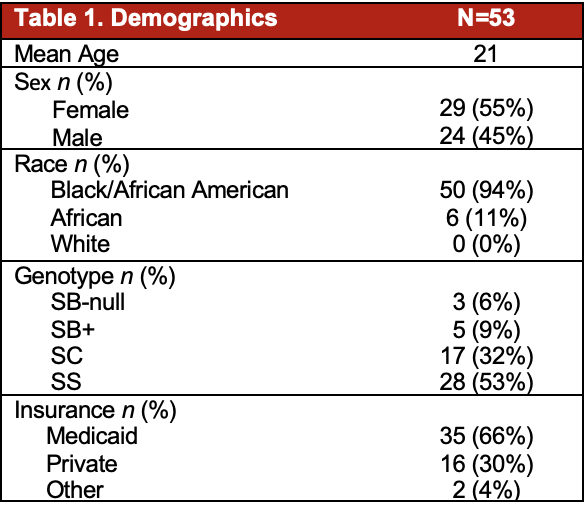

Results: Demographics of the final sample (N=53) are shown in Table 1. The majority were sexually active (62%) and of those, 79% were screened for a STI. Of these, 7 (21%) were diagnosed with ≥1 STI. Few (13%) were provided with education on STI prevention. Two thirds reported contraception use (n=35). Approximately half (n=24) had no documentation of receiving contraception counseling, including 13 sexually active AYAs. Three females had documented pregnancies, with no documentation of counseling on SCD-associated pregnancy risks. Only eight AYAs (15%) received fertility counseling, and less than two-thirds of males received priapism education (n=14). 22 AYAs (42%) received the full HPV vaccine series.

Conclusion(s): Our results suggest that many AYAs with SCD do not receive complete reproductive and sexual health counseling prior to transitioning to adult care. Although most of our sample was sexually active, documentation of contraceptive counseling and use were inconsistent. Further, STI rates in our sample indicate screening and counseling should occur routinely. Given the challenges this population faces during transition (e.g., increased rates of unplanned pregnancy, potential fertility impairment), improving sexual health screening and education may improve transition success. Guidelines on when/how to deliver reproductive health information to AYAs with SCD is a first step towards optimizing their sexual and reproductive health.

Hematology/Oncology

Hematology/Oncology 1

153 - Reproductive and Sexual Health Screening and Education among Transitioning Adolescents and Young Adults with Sickle Cell Disease

Saturday, April 29, 2023

3:30 PM – 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 153

Publication Number: 153.22

Publication Number: 153.22

Divya Shankar, Ohio State University College of Medicine, Dublin, OH, United States; Charis Stanek, The Abigail Wexner Research Institute at Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, United States; Suzy Bangudi, Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, United States; Sophia M. Liles, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, United States; Zachary Colton, Nationwide Children's Hospital, Columbus, OH, United States; Susan E Creary, Nationwide Children's Hospital Research Institute, Columbus, OH, United States; Leena Nahata, Ohio State University College of Medicine, Columbus, OH, United States

Divya Shankar, BS (she/her/hers)

Medical Student

Ohio State University College of Medicine

Dublin, Ohio, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: In the U.S., 100,000 individuals live with sickle cell disease (SCD), an inherited hemoglobin disorder. Most survive into their reproductive years but have worse morbidity and mortality during transition to adult care. During this time, adolescents and young adults (AYAs) also face reproductive and sexual health challenges related to contraception, pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), potential fertility impairment, and priapism. These may be exacerbated by limited access to care and insufficient transition readiness. Yet, little is known about reproductive and sexual health counseling and practices for transitioning AYAs.

Objective: To examine rates of and gaps in reproductive and sexual health counseling for AYAs with SCD prior to their transition to adult care.

Design/Methods: A retrospective review of electronic medical records was conducted of AYAs with SCD at a Midwestern academic medical center that transitioned to adult care between 2015-2019. Abstracted data included sociodemographic information, reproductive and sexual health counseling, and screening practices across AYAs’ entire records before transitioning.

Results: Demographics of the final sample (N=53) are shown in Table 1. The majority were sexually active (62%) and of those, 79% were screened for a STI. Of these, 7 (21%) were diagnosed with ≥1 STI. Few (13%) were provided with education on STI prevention. Two thirds reported contraception use (n=35). Approximately half (n=24) had no documentation of receiving contraception counseling, including 13 sexually active AYAs. Three females had documented pregnancies, with no documentation of counseling on SCD-associated pregnancy risks. Only eight AYAs (15%) received fertility counseling, and less than two-thirds of males received priapism education (n=14). 22 AYAs (42%) received the full HPV vaccine series.

Conclusion(s): Our results suggest that many AYAs with SCD do not receive complete reproductive and sexual health counseling prior to transitioning to adult care. Although most of our sample was sexually active, documentation of contraceptive counseling and use were inconsistent. Further, STI rates in our sample indicate screening and counseling should occur routinely. Given the challenges this population faces during transition (e.g., increased rates of unplanned pregnancy, potential fertility impairment), improving sexual health screening and education may improve transition success. Guidelines on when/how to deliver reproductive health information to AYAs with SCD is a first step towards optimizing their sexual and reproductive health.