Back

Background: Whole exome sequencing (WES) evaluates protein-coding regions of the genome and is commonly used for patients with nonspecific clinical features and conditions with genetic heterogeneity. However, it can miss many pathogenic variants. A non-diagnostic exome does not exclude a genetic diagnosis. Developing a phenotype through history and physical is crucial to selecting appropriate genetic testing.

Objective: We aim to educate general practitioners on the importance of phenotyping and selection of testing.

Design/Methods: 3 patients were identified with significant delay in diagnosis due to improper selection of WES.

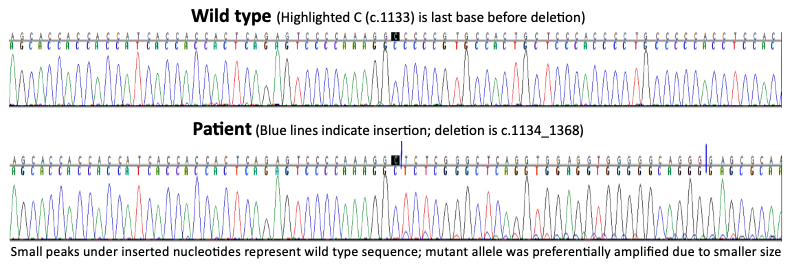

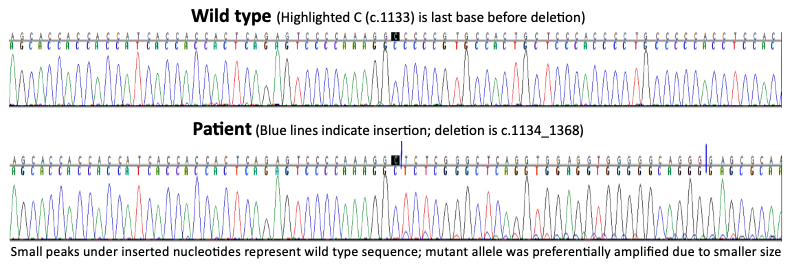

Results: Patient A is a 7-year-old female with global delay, seizures, microcephaly, autism, short stature, hand stereotypies, and ataxia. At 2 years she began head banging, hand wringing, regressing in her language and motor skills. She constantly interdigitates all fingers, lacks speech, and has cold feet. Karyotype and microarray were normal. Trio WES was non-diagnostic 3 times. Mitochondrial DNA and methylation studies for Prader-Willi/Angelman and Russell-Silver syndrome were normal. MECP2 Sanger sequencing revealed a pathogenic indel, diagnostic of Rett syndrome.

Patient B is a 28-year-old male with developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and retinitis pigmentosa. He has tall stature, bitemporal narrowing, high arched palate, dental crowding, long ears, hypoplastic helices, long fingers, hyperextension of interphalangeal joints, long/thin extremities, and pes cavus. Biochemical and genetic testing including WES, and microarray, were non-diagnostic. Mitochondrial DNA testing demonstrated a pathogenic variant in mt-ATP6, m.8993T >G, p.L156R, at 80% heteroplasmy, diagnostic of neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa (NARP).

Patient C is a 16-year-old male born at 35 weeks with NICU care for respiratory support and hypotonia. He has Marfanoid habitus, pes planus, dilated aorta, severe pectus carinatum, scoliosis, hand and foot contractures, camptodactyly, and neuropathy. An aortopathy gene panel, fragile X, Beckwith Wiedemann, trio WES, and mtDNA analysis were nondiagnostic. Microarray revealed mosaicism for a large region of loss of heterozygosity from 14q11.2 to q terminus, diagnostic of mosaic, segmental, paternal UPD14.

Conclusion(s): We report 3 patients with recognizable phenotypes who had diagnostic delays due to incorrect selection of genetic testing. WES can fail to detect pathogenic variants and is not a substitute for accurate and thorough phenotyping. This series reinforces the limitations of WES and the importance of a history and physical to select appropriate genetic testing.

.png)

General Pediatrics: All Areas

General Pediatrics 5

397 - "Hole" Exome - Phenotyping to Fill the Holes in Whole Exome Sequencing

Sunday, April 30, 2023

3:30 PM – 6:00 PM ET

Poster Number: 397

Publication Number: 397.314

Publication Number: 397.314

Robert C. McNamara, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, North Bethesda, MD, United States; Sidney Zven, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center Department of Pediatrics, Annandale, VA, United States; David Horvat, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences F. Edward Hebert School of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, United States; Juvianee I. Estrada Veras, NIH/NHGRI, Bethesda, MD, United States; John P. Schacht, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, United States

Robert C. McNamara, MD (he/him/his)

Pediatrics Resident

Walter Reed National Military Medical Center

North Bethesda, Maryland, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Whole exome sequencing (WES) evaluates protein-coding regions of the genome and is commonly used for patients with nonspecific clinical features and conditions with genetic heterogeneity. However, it can miss many pathogenic variants. A non-diagnostic exome does not exclude a genetic diagnosis. Developing a phenotype through history and physical is crucial to selecting appropriate genetic testing.

Objective: We aim to educate general practitioners on the importance of phenotyping and selection of testing.

Design/Methods: 3 patients were identified with significant delay in diagnosis due to improper selection of WES.

Results: Patient A is a 7-year-old female with global delay, seizures, microcephaly, autism, short stature, hand stereotypies, and ataxia. At 2 years she began head banging, hand wringing, regressing in her language and motor skills. She constantly interdigitates all fingers, lacks speech, and has cold feet. Karyotype and microarray were normal. Trio WES was non-diagnostic 3 times. Mitochondrial DNA and methylation studies for Prader-Willi/Angelman and Russell-Silver syndrome were normal. MECP2 Sanger sequencing revealed a pathogenic indel, diagnostic of Rett syndrome.

Patient B is a 28-year-old male with developmental delay, cerebral palsy, and retinitis pigmentosa. He has tall stature, bitemporal narrowing, high arched palate, dental crowding, long ears, hypoplastic helices, long fingers, hyperextension of interphalangeal joints, long/thin extremities, and pes cavus. Biochemical and genetic testing including WES, and microarray, were non-diagnostic. Mitochondrial DNA testing demonstrated a pathogenic variant in mt-ATP6, m.8993T >G, p.L156R, at 80% heteroplasmy, diagnostic of neuropathy, ataxia, retinitis pigmentosa (NARP).

Patient C is a 16-year-old male born at 35 weeks with NICU care for respiratory support and hypotonia. He has Marfanoid habitus, pes planus, dilated aorta, severe pectus carinatum, scoliosis, hand and foot contractures, camptodactyly, and neuropathy. An aortopathy gene panel, fragile X, Beckwith Wiedemann, trio WES, and mtDNA analysis were nondiagnostic. Microarray revealed mosaicism for a large region of loss of heterozygosity from 14q11.2 to q terminus, diagnostic of mosaic, segmental, paternal UPD14.

Conclusion(s): We report 3 patients with recognizable phenotypes who had diagnostic delays due to incorrect selection of genetic testing. WES can fail to detect pathogenic variants and is not a substitute for accurate and thorough phenotyping. This series reinforces the limitations of WES and the importance of a history and physical to select appropriate genetic testing.

.png)