Public Health & Prevention

Public Health & Prevention 4

355 - Sooner Better than Later: Maternal Mortality Awareness, Communication, and Behaviors among Mothers and Fathers in the NICU from Admission to Discharge

Publication Number: 355.448

Craig Garfield, MD, MAPP (he/him/his)

Professor and Attending Physician

Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine/Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago

Chicago, Illinois, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background: Over 700 women die annually from pregnancy related complications (PRC), with NICU mothers at higher risk. Information seeking behaviors on PRCs, sources of support, and actions taken by mothers and their partners is largely unexplored, especially among the high-risk NICU parent population. Further, given the increased maternal risk for minority women, special attention is needed to understand the needs of traditionally marginalized groups.

Objective: To examine maternal and paternal communication and behaviors related to PRC among a general NICU population.

Design/Methods: English and Spanish speaking NICU parents with expected stay >7 days were asked a series of survey questions as part of a larger, unrelated study. Pilot survey questions were adapted from the CDC’s Hear Her campaign and covered PRC awareness, information seeking, and partner involvement.

Results:

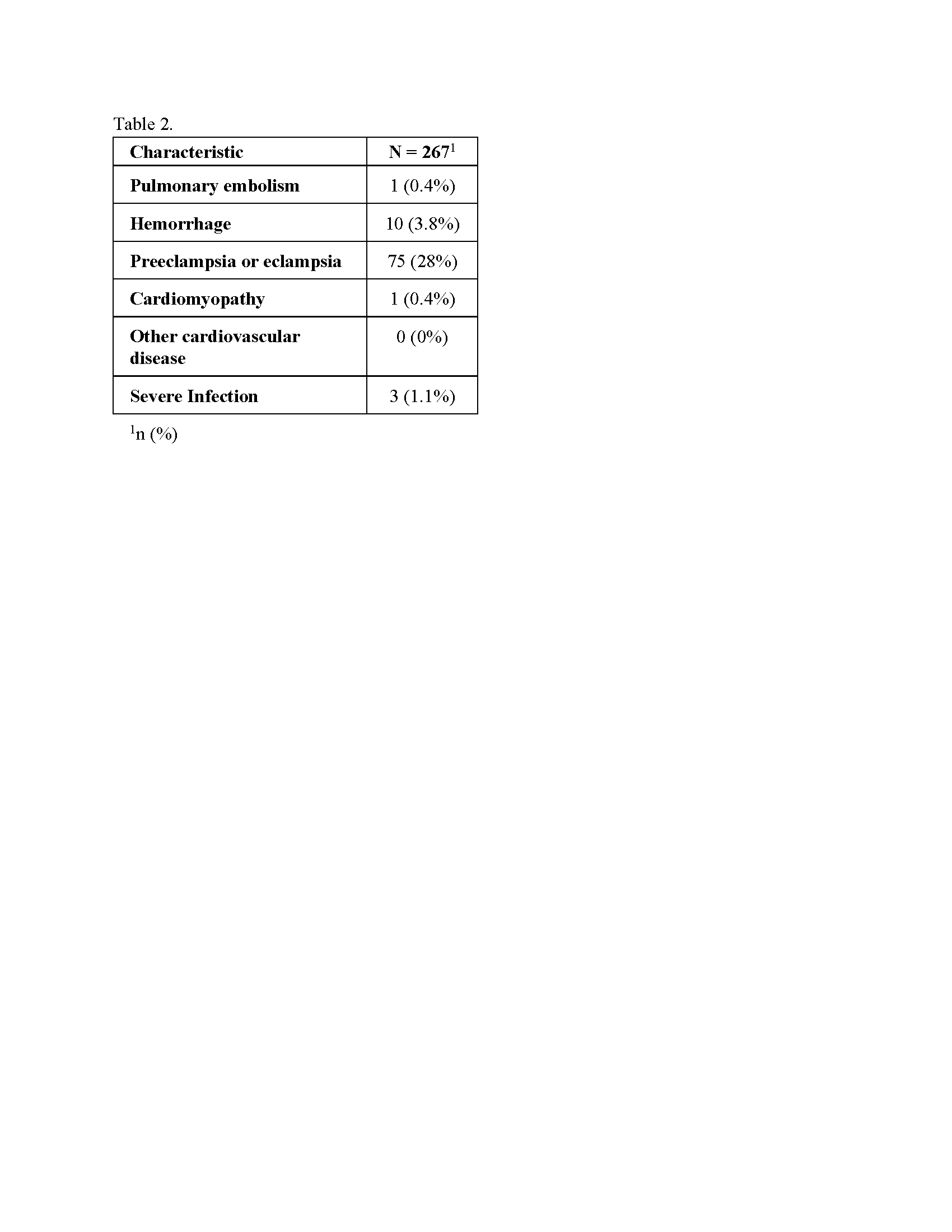

Of 267 mothers and 140 partners, 52% (n=210) were White, 14% (n=56) Black, 20% (n=83) Hispanic and 14% (n=56) Other (Table 1). Furthermore, 33% of mothers had at least one major diagnosis of concern, with pre/eclampsia and hemorrhage most common (Table 2).

Among respondent mothers, 97% talked with their provider “every time/some of the time” when “something just didn’t feel right”. Beyond the provider, the go-to-support-person for mothers who identify as White was the father/partner (65%), a family member (19%), or close friend (12%); among mothers who identify as non-White it was father/partner (50%), a family member (29%), or close friend (14%). Mothers “definitely” would like to receive more PRC information at NICU admission (69%,) and at discharge (68%).

Most responding fathers report mothers discussing PRC with them (65%) and felt “very comfortable” discussing PRCs (75%,). When concerns arose, fathers encouraged her to see her provider (76%), consulted family/friends (49%), and/or searched online (59%). While 26% of fathers “definitely” wanted more PRC information at admission, by discharge only 5.4% did.

Conclusion(s): In a sample at risk for PRC, mothers and fathers discuss PRCs and fathers are most common go-to person for mothers. The window for engaging fathers in PRC information appears to be closer to birth. Supporting both parents in a timely manner may lead to improved maternal outcomes. .png)