Child Abuse & Neglect

Child Abuse & Neglect 1

589 - "The problem’s bigger than we are” - Understanding How Local Factors Influence Child Welfare Responses to Substance Use in Pregnancy, A Qualitative Study

Publication Number: 589.103

Sarah Loch, MPH (she/her/hers)

Director of Research Operations

Vanderbilt Center for Child Health Policy

Nashville, Tennessee, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

Over the past two decades, there has been exponential growth in the number of pregnant people with substance use disorders (SUD), including opioid use disorder, infants diagnosed with neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, and surging rates of infants entering foster care. The rapid increase in infants affected by parental substance use has resulted in substantial strain on family-serving systems, including child welfare agencies. In response, Congress passed an amendment to the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) mandating Plans of Safe Care (POSC) for infants and caregivers affected by substances to ensure wellbeing after hospital discharge. Rollout of this federal change into state policy has lacked uniformity, and quantitative data do not adequately capture implementation facilitators and barriers.

Objective:

This qualitative study explored how local factors (e.g., implementation of policies, collaboration between sectors, training/guidance, local constraints) contribute to variable implementation of federal child welfare policies intended to improve outcomes for families affected by SUD.

Design/Methods:

Using national birth certificate and child welfare data, we identified communities with varying rates of infants entering foster care and birthing parents with Hepatitis C virus at birth (a proxy for injecting drugs/substance use). Casey Family Programs facilitated recruitment of state and county child welfare administrators. Qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews. A hierarchical coding system was developed using the interview guide and preliminary review of the transcripts. An iterative inductive/deductive approach was used for analysis.

Results:

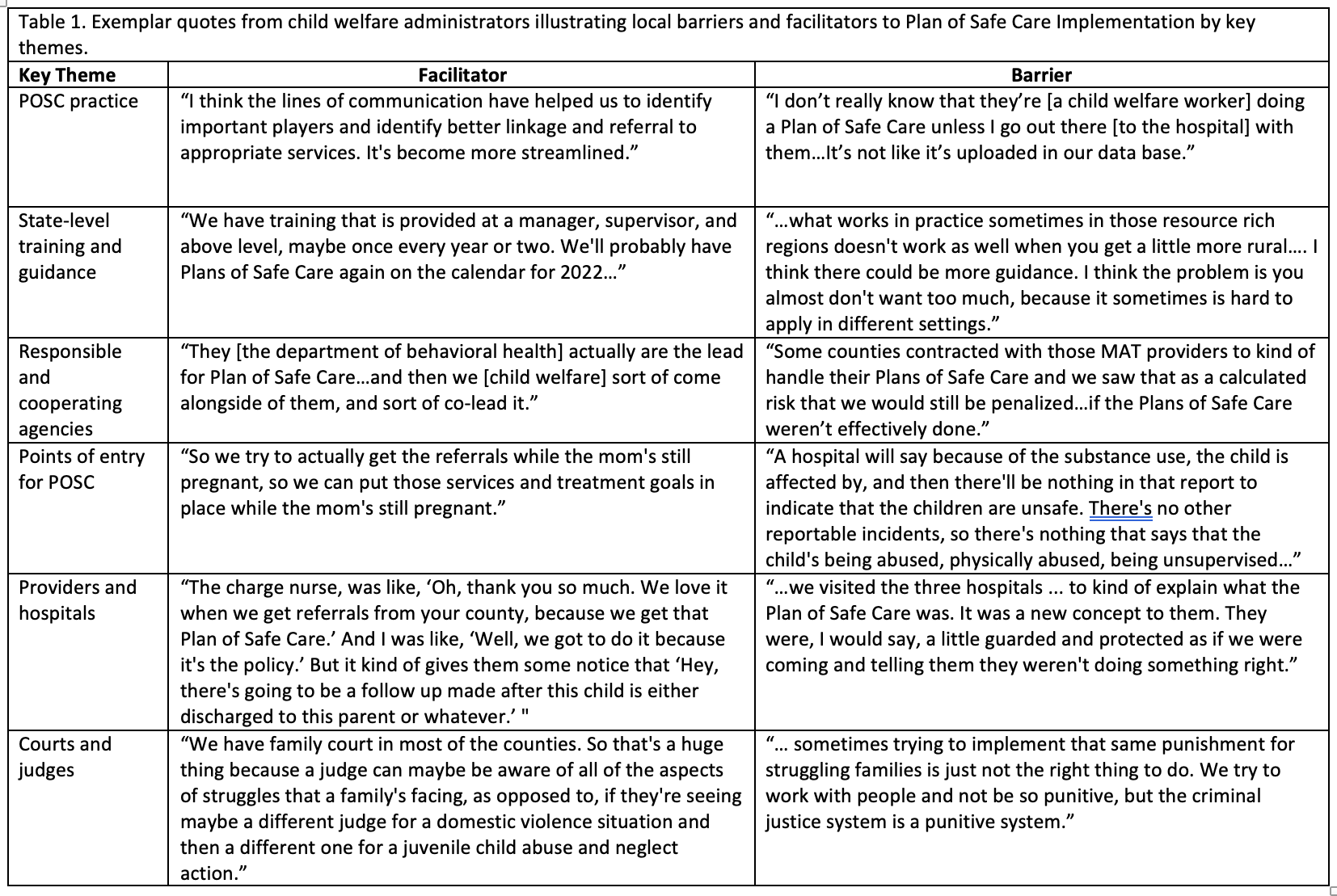

From eighteen completed interviews, six major themes influencing local implementation emerged: 1) POSC practice, 2) State-level training and guidance, 3) Responsible and cooperating agencies, 4) POSC points of entry, 5) Providers and hospitals, and 6) Courts and judges (Table 1). Differences in barriers and facilitators to POSC implementation were evident, including vague POSC policies perceived to be misaligned with meaningful practice, child welfare agency capacity to lead collaboration, healthcare system accountability to policies, and lacking SUD knowledge.

Conclusion(s):

POSC practice is variable and child welfare administrators believe additional support is needed for implementation. As Congress considers CAPTA reauthorization, additional funding, resources, and formal collaboration with key partners such as healthcare professionals are needed to improve outcomes for pregnant people with SUD and their children.