Neonatal Respiratory Assessment/Support/Ventilation

Neonatal Respiratory Assessment/Support/Ventilation 3: Physiology 2 and Clinical Outcomes

341 - Observational study comparing heart rate in crying and non-crying but breathing infants at birth

Publication Number: 341.346

Sara Berkelhamer, MD (she/her/hers)

Associate Professor or Pediatrics

University of Washington School of Medicine

Seattle, Washington, United States

Ashish KC, State University (he/him/his)

Associate Professor

Uppsala University

Uppsala, Uppsala Lan, Sweden

Presenting Author(s)

Co-Author(s)

Background:

Stimulation of breathing infants to elicit a cry is a common practice in newborn deliveries. However, international resuscitation algorithms disagree on whether crying or breathing should guide providing stimulation.

Objective:

Evaluate heart rate in infants who were crying versus non-crying but breathing immediately after birth.

Design/Methods:

This was single-center observational study of singleton vaginally born infants at ≥33 weeks of gestation in Nepal. Infants who were crying or non-crying but breathing within 30 seconds after birth were included. Background demographic data and delivery room events were recorded using tablet-based applications and synchronized with continuous heart rate data recorded by a dry-electrode electrocardiographic monitor. Heart rate centile curves were generated with piece wise regression analysis. Odds of bradycardia (heart rate < 100 bpm) and tachycardia (heart rate ≥200 bpm) during the first 180 seconds after birth were compared using logistic regression.

Results:

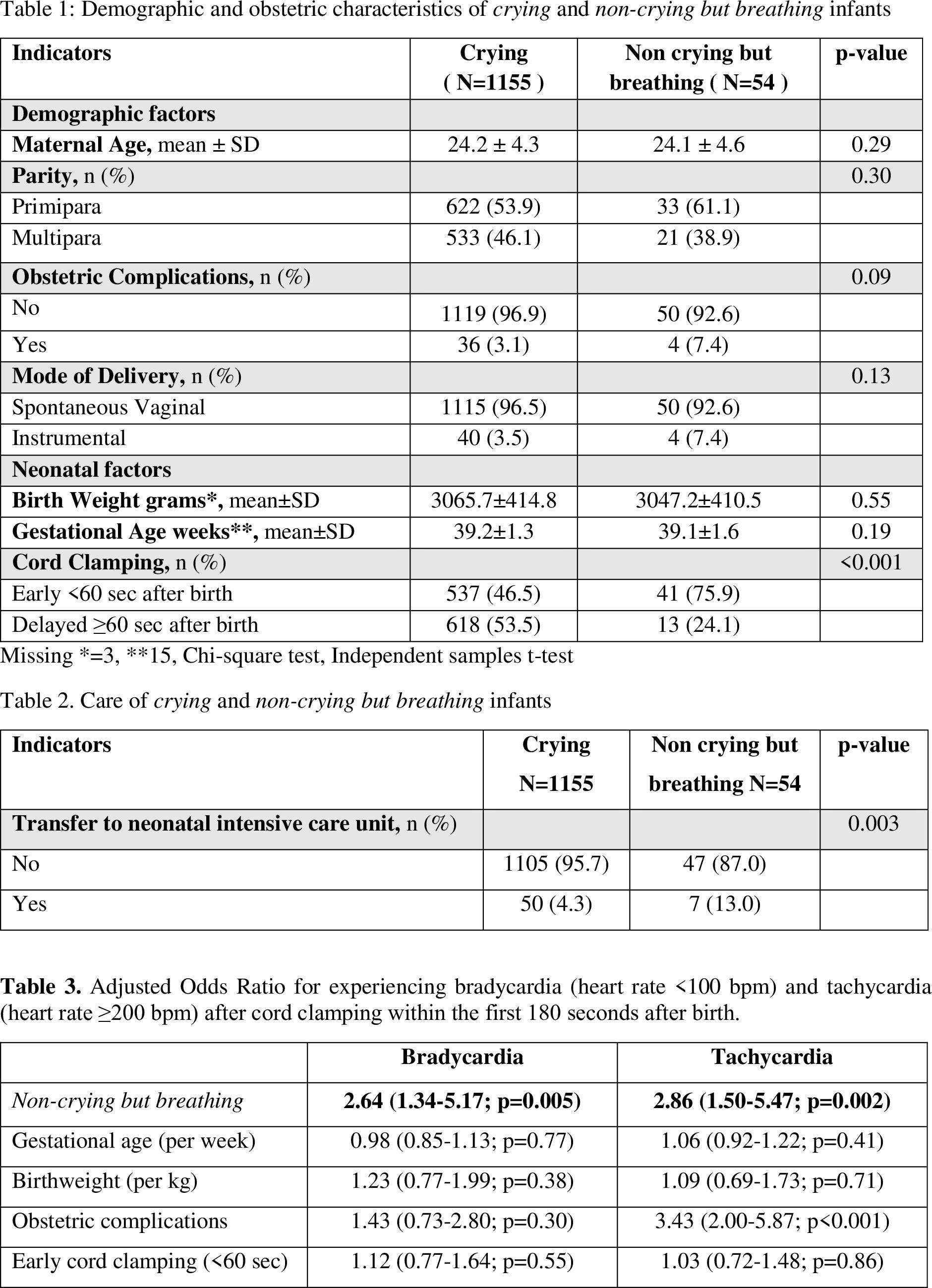

1155 crying and 54 non-crying but breathing infants were included. There were no significant differences in the demographic and obstetric factors between the cohorts (Table 1). Non-crying but breathing infants had higher rates of early cord clamping < 60s after birth (75.9% vs 46.5%) and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit (13.0% vs 4.3%), (Table 1-2). Non-crying but breathing infants had higher odds of bradycardia (adjusted odds ratio 2.64; 95% CI, 1.34-5.17) and tachycardia (aOR, 2.86; 95% CI, 1.50-5.47) (Table 3). Bradycardia appeared early whereas tachycardia was a relatively late phenomenon in non-crying but breathing infants (Figure 2a-b).

Conclusion(s): Non-crying but breathing infants have increased risk of bradycardia, tachycardia and neonatal intensive care admission compared to crying infants. This finding supports that non-crying but breathing infants be closely observed for clinical deterioration. This finding supports that non-crying but breathing infants should not be on the same care pathway as crying, and that close observation of these infants with risk for clinical deterioration is indicated.

.jpg)

.png)