Neonatal Quality Improvement

Neonatal Quality Improvement 5

193 - Reduction of Toxic Noise Levels in NICU

Publication Number: 193.439

Annmarie Gennattasio, DNP, MA, MS, NNP-BC, RNC, C-NNIC (she/her/hers)

Senior Neonatal Nurse Practitioner

Cohen Children's Medical Center

Bellmore, New York, United States

Presenting Author(s)

Background:

The American Academy of Pediatrics states that noise levels in NICUs should be < 45-55 dB. Even short periods of exposure to > 65 dB are detrimental to neonates. Excessive noise can contribute to apnea, hypoxemia, increased oxygen consumption, decreased growth, intraventricular hemorrhage, disturbed sleep rhythm, and hearing loss. High noise levels also negatively impact NICU staff, contributing to impaired efficiency, medical errors, and burnout.

Objective:

In the pre-intervention period, sound levels in our NICU exceeded 65 dB on random 24-hour recordings up to 20% of the time. To reduce harm, we aimed to decrease time > 65 dB to < 5% in both acute and non-acute rooms by Nov 1, 2022.

Design/Methods:

Projects were designed to decrease noise levels: 1) A mandatory on-line multidisciplinary staff educational program, with in-person in-services for NICU medical and consulting staff, 2) Signage about the “Quiet Campaign” with a QR code link to the CDC website on environmental noise exposure, and mechanical improvements to noise from doors and monitors, 3) Rotating placement of “Yacker-Trackers”—visual feedback devices for severity of noise levels resembling a green-yellow-red traffic light, 4) Parent education via brochures with a QR code for a downloadable mobile decibel meter, and 5) Defined “HUSH times” for 2 hours each shift, with dimming of lights, emphasis on quiet, and encouragement of skin-to-skin as appropriate.

Results:

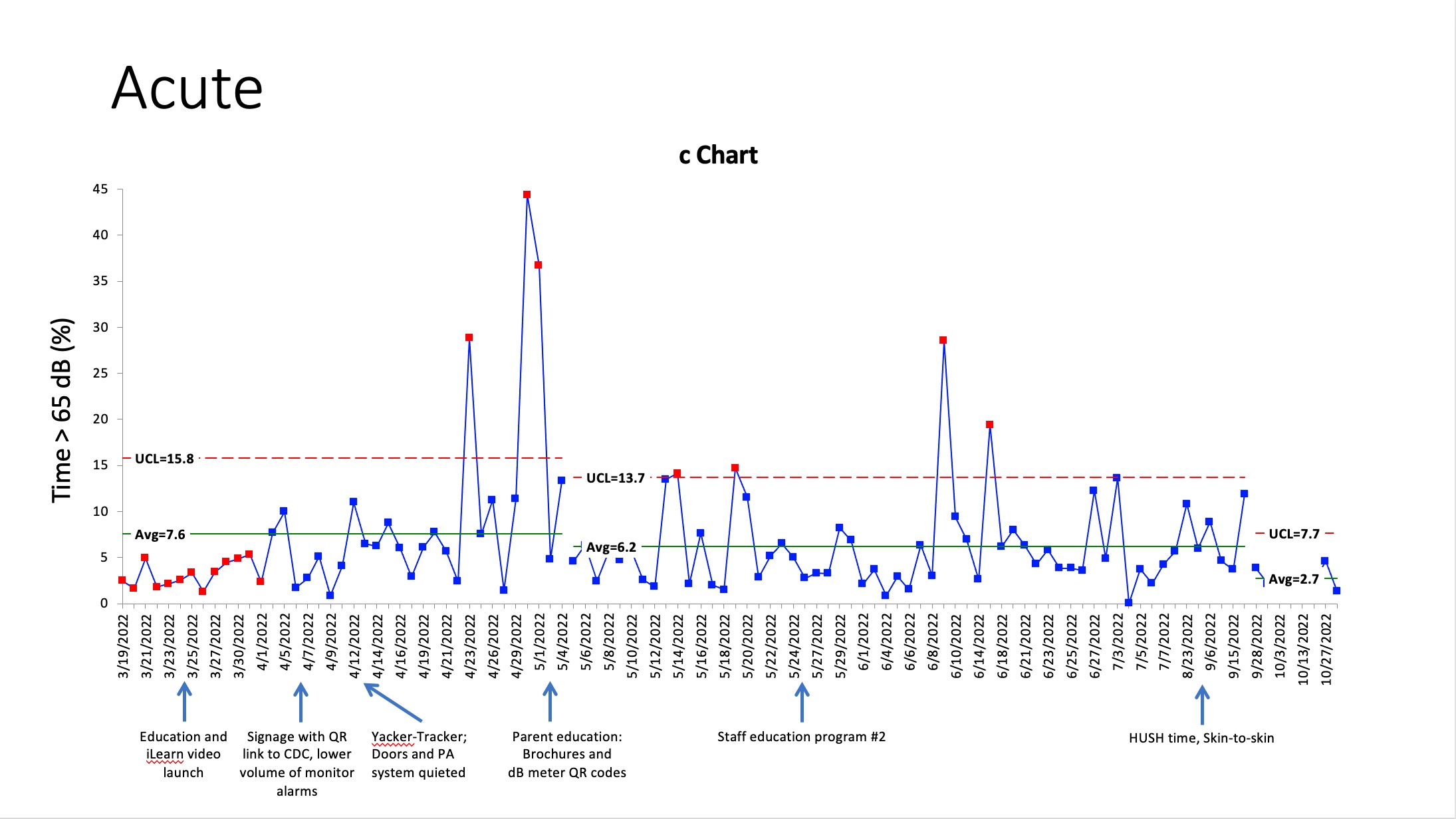

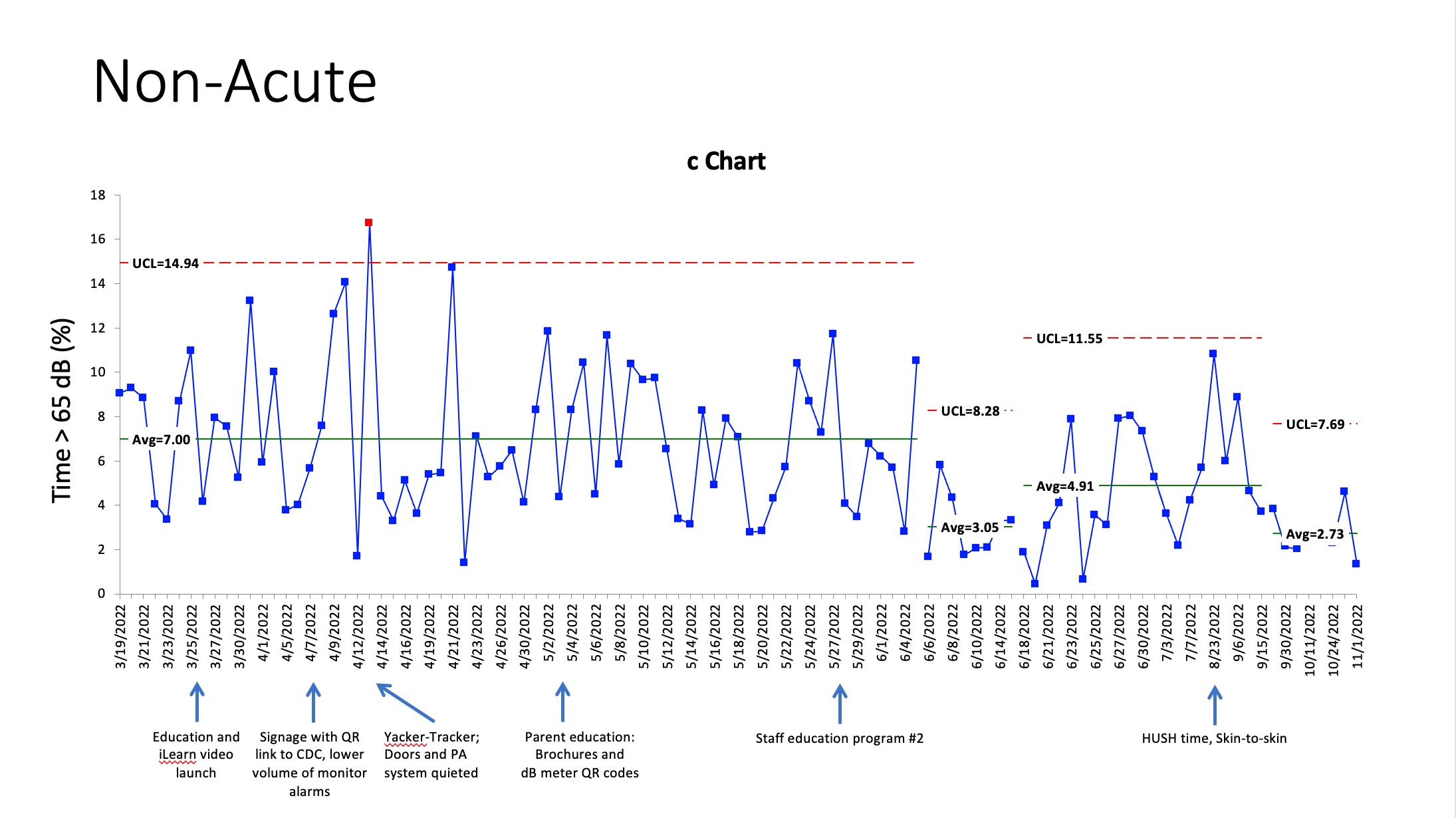

In acute care rooms, mean time > 65 dB decreased from 7.6% to 6.2% in response to parent education with distribution of a link to a mobile dB meter (Fig 1). In non-acute care rooms, reinforcement of staff education led to a decrease from 7.0% to 3.0% (Fig 2). General education via signage, mechanical improvements (monitors, doors, PA), and cues via the Yacker-Tracker alone did not have impact. In both locations, “HUSH times” were associated with significantly lower time at > 65 dB than baseline (p=0.004), and overall mean time > 65 dB decreased to 2.7% in both acute and non-acute rooms after their launch.

Conclusion(s):

Empowering parents by education and personal dB meters can help decrease toxic levels of noise in acute care areas, where maintaining quiet is often a secondary consideration for medical and nursing staff. In contrast, engaging staff has a major impact in non-acute areas, where noise is more easily preventable. Quiet times with skin-to-skin care are effective in both areas, likely related both to the defined hours of quiet and to increased awareness of noise throughout the day.